Lately, I’ve been thinking about completion, about cycles, phases. I’ve been thinking about repetition and revision, how we may pore ourselves into something for hours — even hundreds or thousands of hours — and somehow need to identify, still, the point at which we’re done, finito, complete; about how completeness can feel at once like loss and freedom. Loss because we’re leaving behind that marathon project, putting away those patterns, characters, and events for good. Freedom because we introduce the creative space necessary to pore ourselves into the next project, see the next thing through to completition.

If you’ve been tuning into this writing advice column for a while, you may remember I’m currently learning to play drums. More recently, I’ve been scrutinizing my chosen “teachers,” the selection of songs I’m learning for dexterity, timing, and accuracy while brushing up on my sheet-music reading and handling of syncopation.

Being Capricorn means I can’t possibly settle for your basic run-of-the-mill radio jams. Oh no. Instead, I picked four tracks — one from each of four bands I love and respect — that my musician partner called “ambitious.” (He picked a really nice word to describe my chaotic go-hard-at-stuff-beyond-reach style, but that’s a conversation for another day.) Knowing when my learning for one track is done, though, is relatively easy.

Each learning song is a complete system with a beginning, a middle, and an end. I follow the time signature, count the measures, play the beats, albeit poorly, for now. When I get all the right beats with their accents and nuances in all the right places at album speed, I’ll be done with the song. Doneness, then, has a cut-and-dry meaning, at least for my drum learning. But when it comes to stories, novels, the definition of “done” is a little more amorphous. How do we define “done?” And what does “done” really mean?

So, let’s dissect “done” and the various ways in which we may judge our pieces to be complete.

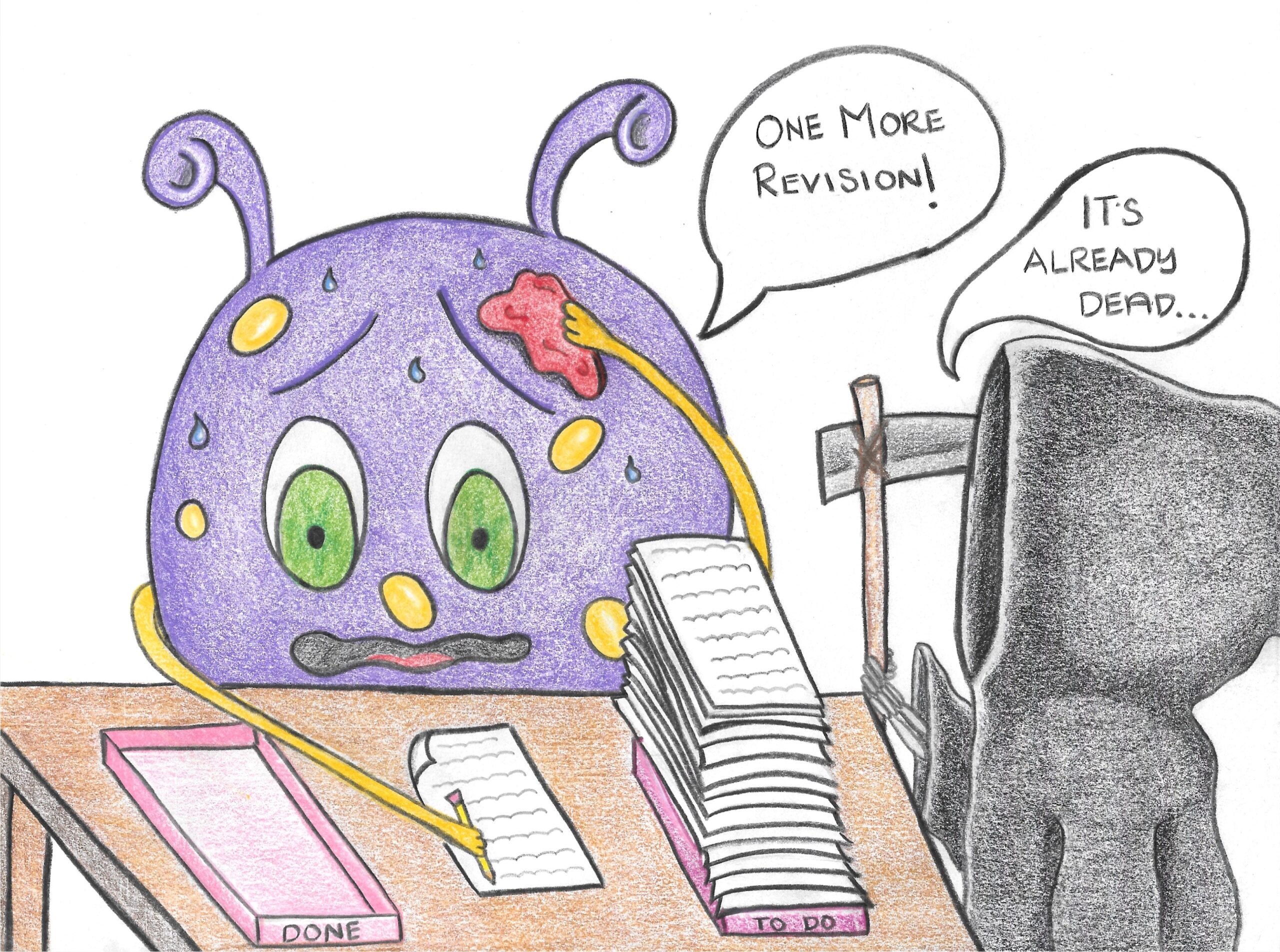

Why it’s dangerous to edit your story after it’s “done”

Philosophically, you may be asking whether any piece of writing is truly done. For aren’t there endless edits, tweaks, to be made — language choices, punctuation, rearrangement? Let me ask you this: Have you ever encountered a severely overworked story?

Here’s an example:

A while back, to familiarize myself with the work of a new-to-me indie publisher, I reached out, asked for help curating a selection of books the publisher believed communicated the breadth, depth, and style of their books within my narrowly defined genre-based wishlist. Selection made, I completed the order, and the books arrived in my mailbox. All good . . . until I cracked open the first book.

Within the collection of short stories, I encountered no fewer than eight similes in the first 100 words (yes, I counted): A simile per sentence for the entirety of the first partial page. Worse, the similes used were all over the place — settings, animals, moods — and created a startling lack of cohesiveness for the opening of the book. I was exhausted in three minutes and had no clue what I’d actually read, what the author was setting up or trying to say. I closed that book quickly and after holding onto it for two years, I’m not sure I’ll ever attempt to read it again expressly because of the overworked prose.

When a story has been severely overworked, the reader — in this example, me — knows, fast. The writing is opaque and strained and may come off as though the author leaned too hard on a thesaurus and not hard enough on craft or authenticity.

When I work with authors on line and language edits, I remind them that the original sentence with that knee-jerk must-get-this-out quality is authenticity. While you may edit the sentence for clarity after writing it, cramming a simile or metaphor into the sentence when it wasn’t part of the original thought is likely to read that way, as something crammed in.

Just like there’s only so much a stomach can hold until the inevitable geyser, there’s only so much a sentence can hold until it breaks open, spews its meaning in indecipherable gook all over your work. To continue working a sentence, paragraph, scene, chapter, story, or novel long after the initial draft is to risk cramming too much into the edited piece and, in the cramming, to kill it entirely.

If you just pictured Chris Farley raging about sales and chicken wings in Tommy Boy (“Oh, my pretty little pet, I love you!”), you know exactly what I’m talking about. And honestly, authors have enough to deal with without killing our own stories.

We must put down the pen and walk away.

How to tell when your story is finished and ready

Now that’ve we’ve unpacked the dangers of overworking your story, editing and revising again and again until we inadvertently strip the soul and voice out of our work, we need to know what “done” looks like. After all, how can we avoid something we don’t understand and can’t look for? Fortunately, knowing when a story is done isn’t strictly intuitive. It can be learned, and taught, and refined over time until your writing process is so smooth that the “done” of one story catalyzes the start of the next, creativity and ideas building upon each other to create your body of work.

First, you must ask yourself the massive question, “Is my story written in the text?” Though this question contains but seven words, together they makeup the bigness of completion: You know when your story is finished when you’ve said what you needed to say within the text on the page. Straightforward, simple perhaps, but not easy.

Because you’re so close to your own story, your pernicious and crafty brain willingly and subconsciously fills in information that is not present on the page but that you already know about your characters, plot, settings, and ideas. Before you can accurately read your story to confirm its doneness, you must take a critical break.

I know, I know. “Put away your story” is old and recycled advice, but it’s honestly the most important part of meaningful revisions, so it’s worth repeating: Put away your story. The amount of time you should take away from your story varies based on story length and other factors. Generally speaking, two days works well for flash fiction, two weeks for short stories, a month or more for novellas and longer works.

Now, there are times when you can’t give yourself the brain break necessary to approach revisions with fresh eyes, such as themed-call submission deadlines, and that’s okay; that’s life in its imperfectness pushing us to adapt and overcome time and again.

After putting away your story, here are three broad guiding questions to get you close to your “done” when analyzing whether your story is written in the text:

Did you ask, and then answer, the big story question?

In an earlier article, I shared how to answer the question your story poses, but now you’re going to determine whether the story question and subsequent answer is present for your readers. Your readers are turning pages specifically to reach the big payoff of your story: Does the mystery get solved?; Do they end up together?; Will they ever leave this place?

Remember that the answer to the question should be intrinsic to the protagonist’s character arc, so check in on your main character. Do they have a clear mission? And do they reach the end of that mission in a satisfying, full-circle way? If you can’t see a clear question early in the story and a clear answer by the end, your reader won’t see it either.

Who is your main character on a granular level?

Character development is such a massive component of storytelling that there are a number of ways to view and analyze your main character, which can be overwhelming. But for the sake of storytelling doneness, we can put character development into three main buckets: Goal, motivation, and conflict.

When assessing your story, look for in-text evidence that communicates your character’s goal (the reason they’re in the story), their motivations for wanting to achieve that goal (the tendrils of personality and stakes that drive the character’s actions forward), and their conflicts (the circumstances, internal or external, that hold your character back from achieving the goal and which force them to choose the hardest and most burdensome paths to reach the end).

Are there questions or uncertainties in each scene?

If your reader doesn’t have a question to answer, they don’t have a reason to keep reading. Tough as it is to hear, them’s the breaks. Those highs and lows, that question-and-answer back-and-forth is what keeps readers turning pages.

When assessing your story for doneness, look for the uncertainty or question that begins each scene (and confirm there is one) and the element of uncertainty left at the end that ultimately sets up the next scene, such that the story undulates with tension. While I haven’t yet written about tension in fiction, ghostwriter, editor, and writer Josh Louis discusses and dissects tension using his own flash fiction.

So, how do you know when it’s time to stop revising? And remember: When you’re done, it’s time to start the next one.

Happy writing!

<3 Fal

Prefer video?

Come hang with me on the MetaStellar channel:

Fallon Clark is a story development coach and editor with more than a decade of experience in communications, project management, writing, and editing. She provides story development and revision services to independent and hybrid publishers and authors spanning genres and styles. And in 2018, she had the joy of seeing Forever My Girl, one of her earliest book projects, on the big screen. Fallon’s writing has been published in Flash Fiction Magazine and The MicroZine. Find her online at FallonClarkBooks.Substack.com, or connect with her on LinkedIn or Substack.