The omniscient person knows all and is a sort of opposite of the first-person narrator, which makes it easy to provide your reader with expansive information. You get to tell the reader exactly what they’re supposed to notice and how they’re supposed to think (though whether the reader should believe you is another topic entirely).

While the omniscient person is technically a third-person POV because it uses “he/she/they” pronouns, as does the objective (which I’ll cover next week), I separate the omniscient into a category of its own for its difficulty to pull off.

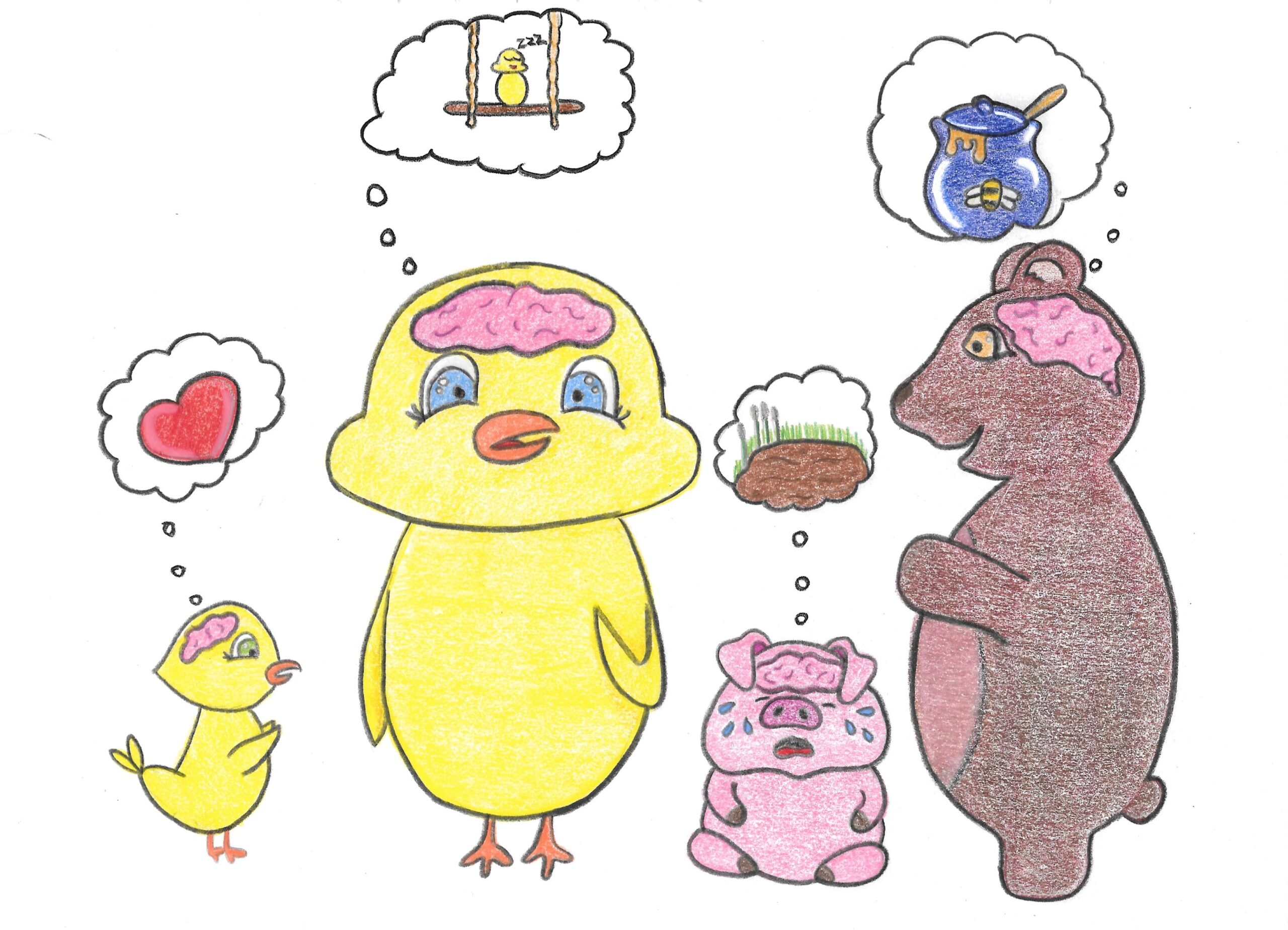

Because while the omniscient person may give the reader access to every character’s thoughts, perceptions, memories, biases, and other emotional and experiential baggage, the omniscient can become impersonal, even jerky, when not handled well.

Instead of being in the head of one character through the novel or through a scene, the omniscient person is written from a detached perspective, can zoom in and out at will, and may sometimes address the reader directly (also known as breaking the fourth wall).

But the detached narrator must have their own voice and role to play.

In this passage from Holes by Louis Sachar, the omniscient narrator is providing the backdrop for much of the novel’s action and is not shy about breaking the fourth wall to do it.

Being bitten by a scorpion or even a rattlesnake is not the worst thing that can happen to you. You won’t die.

Usually.

Sometimes a camper will try to be bitten by a scorpion, or even a small rattlesnake. Then he will get to spend a day or two recovering in his tent, instead of having to dig a hole out on the lake.

But you don’t want to be bitten by a yellow-spotted lizard. That’s the worst thing that can happen to you. You will die a slow and painful death.

Always.

If you get bitten by a yellow-spotted lizard, you might as well go into the shade of the oak trees and lie in the hammock.

There is nothing anyone can do to you anymore.

The protagonist of Holes, Stanley, is a child and can’t know the history of Camp Green Lake, especially since he hadn’t heard of it until he was sentenced to the juvenile detention facility.

But in the referenced passage, the omniscient person addresses the reader directly, encourages the reader to fear the yellow-spotted lizards as much as the narrator does (or claims one should). You can see this in the omniscient person’s use of “you” outside of true second person.

In true second person, “you” is used to make the reader a part of the story, but in the omniscient, “you” is used to tell the reader information they couldn’t otherwise get.

That’s because the omniscient narrator is a storyteller separate from the characters but critical to the reader’s understanding of the characters and the world they live in. And for the reader, the omniscient narrator is the story’s filter.

Still, having an omniscient person to narrate makes sense when delivering the experiences of many characters to your reader at once. It also makes sense when it is the sum of the combined experience that lies at the heart of the story, rather than the personal transformation arc of any one character.

In this passage from Katherine Arden’s fantasy novel, The Bear and the Nightingale, Dunya has just finished telling the children of the household a fireside story before bed:

There was a small, appreciative silence.

Then Olga spoke up plaintively. “But what happened to Marfa? Did she marry him? King Frost?”

“Cold embrace, indeed,” Kolya mutters to no one in particular, grinning.

Dunya gave him an austere look, but did not deign to reply.

“Well, no, Olya,” she says to the girl. “I shouldn’t think so. What use does Winter have for a mortal maiden? More likely she married a rich peasant, and brought him the largest dowry in all Rus’.”

Olga looked ready to protest this unromantic conclusion, but Dunya had already risen with a creaking of bones, eager to retire.

The omniscient person in this passage does two main things:

- qualifies the type of silence for the reader outside of any character’s voice, as indicated by the adjective “appreciative.”

- provides a backdrop for both Kolya’s cheeky statement (intention to speak “to no one in particular”) and Dunya’s rising (her being “eager to retire”).

Since The Bear and the Nightingale is largely about the experience of the household and of the community, providing a multifaceted glimpse into those who live there makes sense.

Just as it allows a wide view of characters within a story, the omniscient person also allows for a wide view of the setting of the story. This allowance of perspective and spacetime allows for dramatic tension to unfold as the reader learns things the characters in the story can’t know.

While the reader learns, they’re invited to see. In this passage from Stephen King and Peter Straub’s horror novel, Black House, a little girl named Irma is missing; many in town fear the worst. The police have no suspects and few clues.

Irma Freneau’s small, inert body seems to flatten out as it intends to melt through the rotting floorboards. The drunken flies sing on. The dog keeps trying to yank the whole of its juicy prize out of the sneaker. Were we to bring simpleminded Ed Gilbertson back to life and stand him beside us, he would sink to his knees and weep. We, on the other hand . . .

We are not here to weep. Not like Ed, anyhow, in horrified shame and disbelief. A tremendous mystery has inhabited this hovel, and its effects and traces hover everywhere about us. We have come to observe, register, and record the impressions, the afterimages, left in the comet trail of the mystery.

Leading up to this passage, the omniscient person has led the reader through town and stopped at several locations to get a lay of the story land. The reader likely has a suspect in mind, and now the reader sees Irma and must wait to find out how long it’ll take the rest of the folks in town to catch up.

While this tension is building for the reader, the omniscient person is calling itself out, including its presence in the reader’s experience. A fellow observer, someone else along for the ride.

Writing & Revising the Omniscient Well

The omniscient person guides the reader, leads the reader through the story landscape, revealing information in bites at a time, talking with the reader as they chew on the information being delivered.

Using the omniscient person allows you to:

- report action from an all-seeing vantage point;

- dip into the mind of any character for general thoughts and intentions;

- interpret the characters’ appearances, speech, actions, and thoughts (even if the characters can’t);

- move freely in spacetime to provide a micro, macro, or panoramic view of the world and its events; and

- provide reflections, judgements, and truths.

Ultimately, the omniscient person allows you to have a conversation directly with the reader, to tell the reader the story, using your voice or another one, as in the examples from Holes and Black House. The omniscient even allows for a quiet voice that slips into the background, like the one in The Bear and the Nightingale.

When writing the omniscient person well, there are a few considerations:

- dramatic irony

- thought portrayal

- narrative voice

Dramatic Irony

Dramatic irony occurs when the reader knows something the characters don’t know. This can be as little as a gesture performed behind someone’s back or as large as an undetected meteor hurtling toward Earth. Or the body of a missing person splayed in a rundown eatery. The literary device helps highlight the differences between the characters’ experiences and the reader’s understanding of those experiences.

While the characters are in the dark, in the omniscient POV (similarly to the objective POV), you can build tension if you give the reader something they can see coming, and give the reader a hint about how the characters may feel when the thing arrives.

In The Bear and the Nightingale, the reader learns to expect the coming of the Winter King. In Holes, the reader learns something about yellow-spotted lizards, suspects they might need to remember those lizards later. In Black House, the reader learns where Irma Freneau is and how bad the situation is for her.

For your book, you must decide whether, what, and when to tell the reader. Keeping hold of certain information until the best point to reveal it is key.

If you’re worried about having delivered enough tension to your reader to keep them engaged, look for moments of dramatic irony.

Questions to ask yourself:

- What does the omniscient person reveal, and why?

- How important is the revelation to the people involved in the story?

- How does the omninscient person’s revelation increase tension for the reader or otherwise alter their experience of the story events?

Thought Portrayal

If there’s one storytelling area where fiction reigns supreme, it’s the ability to get inside a character’s head to get to the source of their internal environment, including their conflicts, reflections, and what incites them to act.

The thoughts of a character help your reader slide into the space behind your character’s eyes and gain a new perspective, even briefly. After all, why read books if we’re not looking for new horizons?

A good practice for character thoughts is that they should reveal more than basic information. They must do double duty and set the mood, reveal or conceal desires, develop the themes, move the action along, and more.

Real people, including you and me, rarely think about what we already know. Humans—and your characters—think about what is happening to them, or what they’re scared of, or what they’re confused by, or what they remember that still carries with it big emotions.

In The Bear and the Nightingale, Kolya’s comment gives the reader a bit of insight into his character, Dunya’s eagerness insight into her age and station.

Questions to ask yourself:

- When your characters reveal thoughts or speak, what do they say?

- How does that information help to characterize the people in your story?

- How do the character’s thoughts advance the scene at hand or the greater story?

Narrative Voice

Books written in the omniscient person have a distinct narrative voice that usually belongs neither to any character in the story nor to the author. Instead, this narrative voice is an unseen persona speaking from the background—a bit like an invisible backseat driver.

But the control of how distinct and obvious that narrative voice is belongs to you.

In Black House, the omniscient person is gossipy and, at times, disconcertingly gleeful. The voice likes the intrigue of small-town mystery for the mystery itself, especially one as juicy as serial murder. The reader who would pick up Black House may have an interest in true crime, murder mysteries, or the like. (Ahem.)

In Holes, the omniscient person nearly slips into the background intentionally, the way one particularly important secondary character (Zero, if you know the story) slips into the background of life. And this omniscient voice has a long-held interest in breaking an old curse and reuniting a family.

When writing the omniscient person, consider who the omniscient person’s voice belongs to. Imagine the character behind that voice even though the reader won’t see them.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Why is the omniscient person telling this story?

- How does the story affect them?

- Should it affect them?

Last Notes on the Omniscient

The omniscient person is great for having a storyteller separate from any single character in the story, and there are lots of reasons you may consider using the omniscient person to tell your story.

When you need to build your story world and reveal background information quickly and efficiently, using the omniscient POV works well. But how well it works may depend on the genre in which you write and the intention behind your story.

If you’re writing horror, speculative, or literary fiction, or offering social commentary or satire, the omniscient person can be a valuable POV to lean on to deliver the right information at the right time to your reader. The omniscient POV gives the reader information with personality, like having a personal trail guide.

And the omniscient person’s filtering may benefit the reader by detaching them from some of the more horrifying aspects of your story, or providing information to the reader that they couldn’t get otherwise from characters who either don’t know or who can’t reasonably comment on that information in context.

But the omniscient person comes with limitations. That same detachment that may benefit the reader in some stories may put them off in others. The reader who picks up a romance novel or a thriller likely wants to immerse themself in the story, to feel the love, to escape the bad guy.

When using the omniscient POV to tell your story, consider how the larger group or community affects or is affected by the story events. Consider, similarly, the role of the omniscient person telling the story. How is the omniscient person affected by the story events?

Taking an analytical view into the “why” of your chosen POV is an important step to ensuring your story is being narrated by the right person for the task.

Happy writing!

<3 Fal

P.S. Have you missed a few POV Deep Dives? Check out the first person, the second person, and the third person.

P.P.S. Check in next week for a deep dive into the objective person.

Prefer video?

Come hang with me on the MetaStellar channel:

Fallon Clark is a story development coach and editor with more than a decade of experience in communications, project management, writing, and editing. She provides story development and revision services to independent and hybrid publishers and authors spanning genres and styles. And in 2018, she had the joy of seeing Forever My Girl, one of her earliest book projects, on the big screen. Fallon’s writing has been published in Flash Fiction Magazine and The MicroZine. Find her online at FallonClarkBooks.Substack.com, or connect with her on LinkedIn or Substack.

Thank you much for this post!