The first person is one of the most common points of view (POV) in novels and has great capacity to deliver immersive reading experiences. It is also the only POV with a true narrator. But your reader will need to know who the narrator is early in the story, so they understand your protagonist.

In the first person, the narrator is the viewpoint character “I” who tells the story. (But nothing can be as simple as that, can it?) First-person POV stories may be centrally or peripherally narrated.

In central narration (we’ll get to peripheral narration in a bit), the narrator is the protagonist, where the “I” tells “my” story. Though popular in fiction, centrally narrated first person is the most common POV for memoir for what I hope are obvious reasons.

The trustworthiness of the narrator, and the reader’s connection to the narrator, depends on how close you allow the reader to get to the narrator’s thoughts and emotions.

Because remember: your narrator is the character. All of the book must be written from the narrator’s perspective and told using their words and their thoughts in their style.

Most of my favorite stories are written in the first person with a central narrator, and most get up close and personal, providing insights into the narrator’s emotions as they tell their story.

Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen uses a first-person narrative style that allows the reader to become intimate with Jacob, the book’s central narrator, as he processes the realities of circus life and falls in love with a woman he’s not supposed to love.

My jaw moves, but it’s several seconds before anything comes out. “Marlena, what are you saying?”

When I look up, her face is cherry red. She’s clasping and unclasping her hands, staring hard at her lap.

“Marlena,” I say, rising and taking a step forward.

“I think you should go now,” she says.

I stare at her for a few seconds.

“Please,” she says, without looking up.

And so I leave, although every bone in my body screams against it.

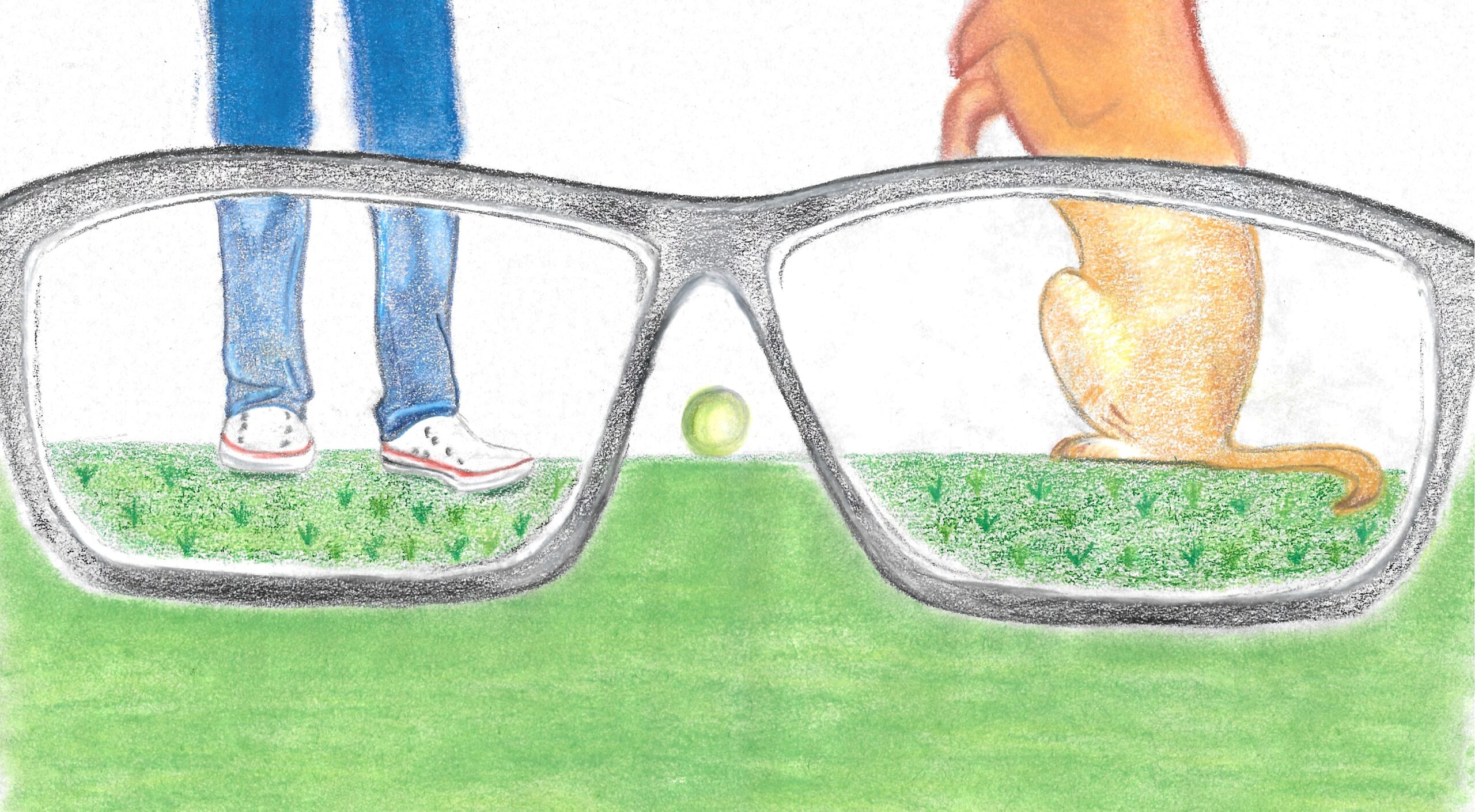

In the passage from Water for Elephants, the first-person style means the reader can feel what Jacob feels—or something similar, drawing from their own life experiences—because they see the circus politics through Jacob’s eyes.

And some stories go a bit further, pulling the reader into the “I” narrator’s experience so completely that the narrator doesn’t have a name of their own, such as in The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood:

“Blessed be the fruit,” she says to me, the accepted greeting among us.

“May the Lord open,” I answer, the accepted response. We turn and walk together past the large houses, towards the central part of town. We aren’t allowed to go there except in twos. This is supposed to be for our protection, though the notion is absurd: we are well protected already. The truth is that she is my spy, as I am hers. If either of us slips through the net because of something that happens on one of our daily walks, the other will be accountable.

Notice how, in the passage above, the narration slips easily between the first-person singular “I” and the first-person plural “we,” which, in context, shows the reader how easily the individual gets lost in the collective, how dangerous individuality can become, which is at the heart of the novel.

There are many books that break from the intimacy of first-person stories, one of which is Bret Easton Ellis’ novel, American Psycho, which uses a first-person central narrative style that is distant.

However, this distance between reader and narrator is intentional, as the reader finds out, and Ellis chooses language that keeps the reader an arm’s length away from Bateman.

“The sushi looks marvelous,” I tell her soothingly.

“Oh it’s a mess,” she wails. “It’s a mess.”

“No, no, the sushi looks marvelous,” I tell her and in an attempt to be as consoling as possible I pick up a piece of the fluke and pop it into my mouth, groaning with inward pleasure, and hug Evelyn from behind; my mouth still full, I manage to say “Delicious.”

In American Psycho, the reader experiences the world through Patrick Bateman’s eyes, but the references to “I” are rather sparse in the dialogue-heavy novel. And when the reader gets “I” statements, most are devoid of any emotional reaction to the scene at hand, unless Bateman is attempting to project a specific emotion in a social setting.

In fact, Bateman’s true emotions are rather limited, given that he is a psychopath: jealousy over material things or social status; anger at any test of his intelligence; reverent glee when discussing Genesis; disdain for those he views as lesser than he.

Beyond central narration, the narrator may tell a story about someone else, and using this peripheral narration style, the first-person narrator may be either the singular “I” or the plural “we.”

In The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, the narrator is Nick. And Nick says about Gatsby early on:

If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about [Gatsby], some heightened sensitivity to the promises of life, as if he were related to one of those intricate machines that register earthquakes ten thousand miles away. This responsiveness had nothing to do with that flabby impressionability which is dignified under the name of “creative temperament”—it was an extraordinary gift of hope, a romantic readiness such as I have never found in any other person and which it is not likely I shall ever find again.

In the passage from The Great Gatsby, it’s clear that the viewpoint narrator, Nick, is not the protagonist of the story. Jay Gatsby is.

The reader is left to determine how truthful Nick may be in his qualifications of and general disposition toward Gatsby as the novel progresses.

Writing & Revising the First Person Well

Writing the first person well means choosing the type of narration most pertinent to your story, as well as the right narrative distance, and then making sure you adhere to it.

Since you want to give your reader an immersive experience through your novel or memoir and you’ve chosen the first person to deliver your message, you’ll want to ensure you remain firmly within your chosen narration style:

- central narration

- peripheral narration

Central Narration

Remember that in central narration, the narrator is the protagonist, where the “I” tells “my” story or the “we” tells “our” story.

The trustworthiness of the narrator (and the reader’s connection to them) depends on how close you allow the reader to get to the narrator’s thoughts and emotions.

Consider how much you want your reader to know and how much the “I” is willing to share.

Then, let your reader get up close and personal.

Central Narrative Distance

When writing the “I/we” as a central narrator, you’ll most effectively pull the reader into the story by closing the gap between author/character and narrator as much as possible.

To get your reader as close to the narrator as possible, challenge yourself to remove sensory filters—phrases like “I/we saw,” “I/we heard,” “I/we smelled,” “I/we tasted,” “I/we touched,” “I/we felt,” and others.

Get the character’s thoughts as close to stream of consciousness as you’re able without going off on wild, unrelated tangents.

This way, the reader gains insight into what the character is thinking, how the character is processing the events unfolding, which will build trust. Or not.

Questions to ask yourself:

- What does the narrator notice in the moment, and why?

- How will I show the reader how the narrator is feeling in this moment?

- How will the narrator’s experience shape the reader’s understanding of my book and its core message?

Peripheral Narration

Remember that in peripheral narration, the narrator (often “I” but sometimes “we”) tells the story about someone else.

Often, the peripheral narrator is a side or main character, but they are not the protagonist. They report on the events of the true hero (or anti-hero).

Consider how much control you wish to have over the reader’s perception of your story as it unfolds and how much your narrator must know about the protagonist or the world to retain that control.

Peripheral Narrative Distance

When writing the “I/we” as a peripheral narrator, you may serve the reader well by limiting the narration to a more passive storyteller who remains as objective as they are able, even as they learn and grow and change through the stories they tell about the protagonist.

Consider what the narrator could reasonably know within the limits of their experience and humanity, though they may speculate or interpret as needed.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Why is my narrator interested in or fascinated by the protagonist?

- What assumptions, interpretations, and speculations does the narrator make, and are they correct?

- How does the narrator’s storytelling help shape their understanding of not only the protagonist but of themself?

Last Notes on the First Person

The reader is not required to accept the narrator as trustworthy and is not required to accept the narrator’s assumptions, interpretations, or speculations. In fact, it can benefit the story if the reader rejects the narrator’s opinions to form their own.

When in doubt about using the first person, consider whether you want the narrator to be reliable or unreliable, central or peripheral to the plot events, and go from there.

And remember: because the first-person narrator is the character, your authorial voice should not leak into the story. Choose words and a syntactical style specific to your narrator’s voice.

Happy writing!

<3 Fal

P.S. Check in next week for a deep dive into the second person!

Prefer video?

Come hang with me on the MetaStellar channel:

Fallon Clark is a story development coach and editor with more than a decade of experience in communications, project management, writing, and editing. She provides story development and revision services to independent and hybrid publishers and authors spanning genres and styles. And in 2018, she had the joy of seeing Forever My Girl, one of her earliest book projects, on the big screen. Fallon’s writing has been published in Flash Fiction Magazine and The MicroZine. Find her online at FallonClarkBooks.Substack.com, or connect with her on LinkedIn or Substack.