“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” So said H. P. Lovecraft, and he drew on that fear to become one of the most influential horror writers of all time, perhaps second only to Edgar Allen Poe. A host of contemporary writers continue to build on the mythos he created, and Lovecraft’s own stories are still being adapted into movies and graphic novels. Yet even his most ardent fans shudder at Lovecraft’s racism. He loathed and feared people whose features or languages marked them as outsiders. His stories blend mind-destroying cosmic horror with lyrical beauty, but to a modern reader the racism itself is also a horror.

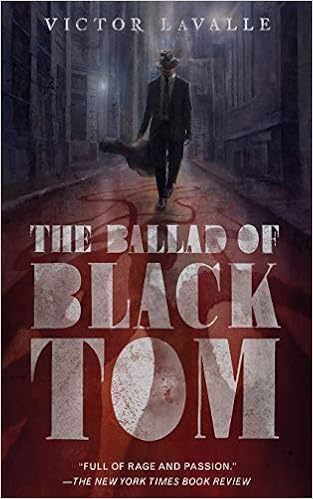

As someone who loves the descriptive prose and unabashed romanticism of Lovecraft’s stories, I am heartened by a handful of writers working within the mythos today who, instead of trying to wipe away the racism have faced it head-on, holding it up to a mirror to show us its backward reflection. Black author Victor LaValle is one such writer. His black protagonists live in a racist world — as do we all — and the dangers posed by that are part of what they must survive, along with eldritch horrors from the cosmic void. He dedicates his novella “The Ballad of Black Tom,” “for H. P. Lovecraft, with all my conflicted feelings.”

When Lovecraft moved from his beloved Providence to New York City in the 1920s, that “oldest and strongest kind of fear” he experienced was of his Brooklyn neighbors. “The population is a hopeless tangle and enigma,” he says in “The Horror at Red Hook,” “Syrian, Spanish, Italian, and negro elements impinging upon one another… It is a babel of sound and filth, and sends out strange cries to answer the lapping of oily waves at its grimy piers and the monstrous organ litanies of the harbour whistles.” Ruthanna Emrys and Anne Pillsworth call this “Lovecraft’s Most Bigoted Story,” though there is some stiff competition for that distinction.

Lovecraft’s racism wasn’t just incidental. Forced to rub elbows with polyglot foreigners, the writer shows the same mix of revulsion and fascination as that story’s protagonist, the racist Irish-American cop Thomas Malone. New York’s immigrant communities “chilled and fascinated him more than he dared confess to his associates on the force, for he seemed to see in them some monstrous thread of secret continuity; some fiendish, cryptical, and ancient pattern utterly beyond and below the sordid mass of facts and habits and haunts.” The character is a mystic, the author a rationalist, but we can see both of them cultivating their fear, carefully nurturing it for the secrets it may reveal to one or the stories it might engender in the other. Fear of the unknown is part of the cultural and emotional bedrock on which racism is built. If we live our lives in a small circle of firelight surrounded by a bulwark against the darkness and chaos beyond, then it may not matter if the chittering voices in the shadows come from space aliens, infernal demons, or — as in “The Horror at Red Hook” — illegal immigrants. Fear of the unknown is easily transferable.

The first half of “The Ballad of Black Tom” is told from the viewpoint of Charles Thomas Tester (Tommy to his friends), a young black street musician with no talent who hustles for a living by procuring obscure occult texts for dangerous clients. One day he encounters Robert Suydam, who offers him an outrageous amount of money to play for him at a gathering at his house three nights hence. Tommy is hesitant. He has a run-in with Thomas Malone, the racist white cop portrayed with chilling realism. (In today’s world, Malone could easily have stood in for Derek Chauvin.) Malone shakes him down and warns him to stay away from the neighborhood. Tommy’s father also advises him not to go back; Flatbush is a dangerous place for a black man to be after dark, and any invitation into the house of a rich white stranger is dangerous. Tommy takes the gig and in the second half of the book he’s working for Suydam, calling himself Black Tom and serving as a sort of personal assistant. Suydam is preparing for a momentous ritual to take place in the tenement basement but Tommy, shaken by earlier events in the book, has his own agenda.

The second half of the book is told from Malone’s point of view. As in the original story, Red Hook is Malone’s regular beat, where he wages a perpetual battle against bootlegging and smuggling rings while keeping an eye on occult activities as well. His raid on the tenement is the ultimate no-knock warrant with a militarized police force, but even the heavy anti-aircraft machine guns set up across the street and trained on the tenement entrances don’t clue us in to the full extent of the cataclysm about to unfold.

LaValle, with four novels, two novellas, and a comic book series to his name, is a master of atmospheric horror and The Ballad of Black Tom is a gripping read. I finished it in a day and a half but at about 150 pages, a quick reader might down it in one sitting. It holds all the horror of the cosmic void that has made the Lovecraft mythos such an enduring cultural artifact, placing it deftly amid the very real terrors of life for a young black man in a racist society.

Peter Cooper Hay is the pen name for Peter Bishop. He’s a retired science teacher, a Quaker, and a Wiccan/Pagan, and his eclectic background comes through in his writing, where hard science can weave together with mysticism, magic, and political intrigue. He lives with his wife in a ramshackle farmhouse in western Massachusetts, and when he's not writing he can usually be found in his workshop playing with his power tools.