Sci-fi and fantasy magazine editors are discussing charging submission fees, changing submission schedules, limiting submissions to known authors, using AI-detection tools, and considering other means to combat AI spam.

For those who’ve missed the debate so far, Clarkesworld, the top global science fiction and fantasy magazine by traffic, has temporary stopped accepting new short story submissions because of a flood of AI-generated spam.

This is where scammers, thinking they’re going to get rich quick, use ChatGPT and similar tools to generate barely-readable content and submit it in large volumes to fiction magazines. The hope is that editors will like these pieces, publish them, and pay money for them.

Many science fiction and fantasy magazines do, in fact, pay for stories. But these payments tend to be low and acceptance rates are even lower.

The AI-generated stories created by spammers by the truckload are simplistic, formulaic, and barely readable but their sheer volume is making it difficult for editors to find stories that are actually worth publishing.

Not all magazines are seeing the spam, though. Smaller markets in particular may not be on the spammers’ radar.

“We may have had some suspicious submissions but haven’t been spammed as the target of any coordinated scam so far,” said Tyler Berd, managing editor at sci-fi magazine Planet Scumm. However, it’s next open submission window isn’t until the summer.

He thinks it’s fitting that science fiction magazines are the ones dealing with the problem of AI-generated spam, because the issue of AI creativity is “something sci-fi has been thinking about loud about for so long.”

Still, he and other sci-fi and fantasy magazine editors are gearing up for a potential onslaught and debating how to address the issue.

So far, all proposed solutions have been problematic in that they can hurt legitimate writers or put undue burdens on the already-stressed editorial staff. The ideas proposed so far include charging submission fees, adding restrictions on how or when people can submit, or using AI detectors in an attempt to weed out spam.

Charging fees

Science fiction and fantasy magazines do not, as a rule, charge writers to submit stories.

This may have to change, some editors say, though others worry that it will discourage new and disadvantaged writers.

“I don’t think pay-to-submit sacrifices legit writers,” said Fran Eisemann, editor at Cosmic Roots and Eldritch Shores, which is open for submissions the first and second day of each month. “I think a $1 submission fee would help validate the submitter as a real person submitting non-AI work, without stressing anyone’s budget.”

The submissions fees could be used to increase payment rates to authors, she added, or to accept more stories, or both.

“Most publishers are putting in tremendous time and effort to bring stories to readers, while they and their staffs may not even be breaking even, or are in the negative income bracket,” she said. “So $1 is not too big a sacrifice to help insure that real writers will be getting paid, instead of the owners of machines generating text plagiarized from real writers.”

For disadvantaged writers, it would be easy to allow those in dire straights to request a fee waiver, she added. “An AI spammer is unlikely to take the time to make such a request.”

There was a time when speculative magazine publishers were profit-making businesses that sometimes took advantage of writers, she said. That’s where the “writers never pay” philosophy originated.

“Now, when many publishers and their staffs, especially online ones, work for free, or at a monetary loss, I don’t think the same philosophy strictly applies,” she said.

“This is a non-starter,” said Morris Allen, editor and publisher of Metaphorosis, which is always open for submissions. “As an editor who rejects most stories and a writer many of whose submissions are rejected, I think submissions fees of any size are a substantial barrier to most writers.”

If he had to pay even $1 for every submission he made to magazines, he himself wouldn’t be much above breaking even most of the time, he said. “I could afford it, but I likely wouldn’t do it.”

Charging for submissions could also land a speculative fiction magazine in hot water with the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association, which is heading in the opposite direction.

“SFWA standards aren’t the only standards, but they are important,” said Allen.

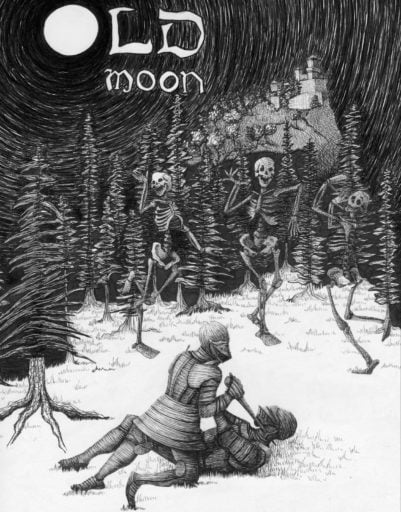

Submission fees are a non-starter, agreed Graham Thomas Wilcox, assistant editor at Old Moon Quarterly, which had its submission window this past January.

“Many of our submissions at Old Moon come from new, or newer, authors, and we also receive a significant — and growing — contingent of submissions from countries such as Nigeria and Ukraine,” he said. “Not a few of these nations are ones that often experience significant issues with PayPal and other online vendors due to high rates of fraud.”

By charging submission, all those writers would be essentially locked out of publication.

“And speaking as a newer venue,” he added, “We’d essentially kill our magazine in its infancy by charging submission fees. Almost all science fiction and fantasy authors — established and otherwise — view them as a sign of disrepute, and refuse to submit to such markets.”

Selena Middleton, publisher and editor at Stelliform Press, said that she hopes that the industry will be able to find another way forward.

“I would not pay even as low a fee as $1 to submit,” she said. “I might make an exception for a contest with a very high level of prestige, but I would not include pay-to-submit venues in my regular stable of magazines to submit to.”

Charging for submissions would exclude many legitimate writers, she said, including those from the working class or from marginalized communities.

“I’m strongly opposed to submission fees,” agreed Fred Coppersmith, editor and publisher of Kaleidotrope, which is currently closed to submissions. “Even if they appear low, even if they’re just a token payment, they will absolutely discourage writers — especially if they start to encounter those fees every time they resubmit a piece somewhere new. Even writers who are perfectly willing to pay submission fees may encounter significant roadblocks when doing so, like currency conversions, the inability to send money from or to certain countries, or just not wanting to sign up with a service like PayPal.”

Plus, having to set up a payment system and confirm that each submission corresponds to a paid fee would significantly complicate his job as editor, he said.

“Right now, I’m still taking submissions directly via email,” he said. “I don’t think I’d be able to continue doing that, at least not easily, if I added fees to the equation. And all of this assumes that submission fees even would work as a deterrent to people submitting AI-generated work, which I don’t think is in any way guaranteed.”

Submission windows and other barriers

Clarkesworld has continuous submissions — writers can submit stories at any time, without waiting for a submission window to open. There’s speculation that AI content spammers are targeting continuous submission publications first, so one possible idea to combat spam is to make submission windows narrower.

“I agree with using shorter windows,” said Kevin Frost, host of the Gallery of Curiosities podcast, which features original horror stories and is currently open to submissions.

The flood of spam submissions usually shows up towards the end of a submission window, he added. “That’s when the ‘write for money’ sites find and index you.”

Metaphorosis’ Allen is not a fan of shifting or shrinking submission windows.

“If they’re an obstacle to spammers and AI-assisted writers, they’re an obstacle to human writers as well,” he said. “As a writer, I personally put venues with shifting or unpredictable submission windows in a second or third priority category, especially if the window fills quickly or unpredictably.”

There was one magazine that opened for submission one day a week and quickly filled its quota.

“After trying many times, I essentially gave up on that market entirely,” Allen said. “I’m not going to build my schedule around one magazine.”

Trying to track multiple windows at different magazines? Even harder.

“If they become too unpredictable, Submission Grinder or someone else will make a tool to manage them, and then the benefit is gone,” he said.

Similarly, if, say, only newsletter readers are notified about submission windows, then new writers will lose out, as will writers who only have intermittent Internet access.

“We’ll see even more of the same old names over and over,” he said.

MetaStellar has two annual submission windows for original fiction, one coming up next month. Reprints are accepted at any time, as are essays and reviews.

AI detection tools

Another approach to detecting AI spam is to use AI-detection tools to try to weed it out AI-generated content. There are several free AI detection tools available, though most don’t work at all.

“It’s not reliable enough now, and I don’t believe it will be in future,” said Metaphorosis’ Allen.

Paid tools might be able to do a better job, but Allen said that his magazine doesn’t have the money to spend on them — nor the time to use them.

MetaStellar, after a great deal of internal debate, decided to allow AI-assisted writing. But that doesn’t mean that we want to see a flood of AI-generated spam either. Good stories take time and effort.

Editorial guidance

Metaphorosis’ Allen said he doesn’t have any good answers to the problem of AI spam, except possibly one — having a substantial editorial revision process in place, which Metaphorosis does.

“That in itself is a barrier to AI-dependent authors but not to committed humans,” he said.

It is very difficult to get an AI to make specific changes to a story — it tends to want to wander off in its own direction.

Because of this, he’s not personally worried about being flooded with spammy AI stories. For now, at least.

“In future, it may not be possible to distinguish between an author relying on AI for writing and edits and an author who resists even the smallest of changes,” he said. “But I don’t think we’re there yet.”

MetaStellar editor and publisher Maria Korolov is a science fiction novelist, writing stories set in a future virtual world. And, during the day, she is an award-winning freelance technology journalist who covers artificial intelligence, cybersecurity and enterprise virtual reality. See her Amazon author page here and follow her on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn, and check out her latest videos on the Maria Korolov YouTube channel. Email her at maria@metastellar.com. She is also the editor and publisher of Hypergrid Business, one of the top global sites covering virtual reality.

Regarding:

“Not a few of these nations are ones that often experience significant issues with PayPal and other online vendors due to high rates of fraud.” By charging submission, all those writers would be essentially locked out of publication.”

— I know the difficulties of sending payments to Nigeria, and a couple of other countries, so I imagine payments from those places could be difficult or impossible to make. Those countries can be identified and exceptions made.

Some people think submissions from SF/F writers belong in a special category, and charging fees to writers in these specific genre is wrong. Whatever the history for that, it really makes no sense today.

from Morris Allen: “If he had to pay even $1 for every submission he made to magazines, he himself wouldn’t be much above breaking even most of the time, he said. ”

— I am impressed with Morris’ writing speed, that he can send out so many stories that $1 submission fees would leave him hardly breaking even.

It would be interesting to do a survey of writers and see how many stories they send out per month vs. how many acceptances they get.

“having to set up a payment system and confirm that each submission corresponds to a paid fee would significantly complicate his job as editor”

— There are submissions systems that automatically take care of that.

Fran

Setting aside Yog’s Law and the history of writers’ scams (in commercial/genre fiction as well as the literary space where fees are not an automatic non-starter) for the moment, equating “breaking even” to “writing speed” makes zero sense. Most stories rack up their share of rejections before they find a home.

Morris Allen is spot on. Even a slow writer is unlikely to sell a story on the first submission. Some take dozens of submissions to sell, some can sell after upwards of fifty rejections. By the time you sell a story for semi-pro pay, if you’ve put 50 dollars into it, your payout on that story is significantly reduced. It’s not about speed of writing, it’s about the fact that most stories don’t sell to the first place submitted. A dollar sounds reasonable, until you factor in paying that over and over and over just to get a small sale in return.

Long term fees just aren’t beneficial to the writer. It seems to me that most publications could use a verification system to see if a story was written by a person or not.

Other than that, I think editors may have to accept the reality of legitimate submissions that were created by a human author using an AI.