Can we create artificial gravity?

As a kid, I filled a bucket with water and swung it on a rope in a vertical circle – the water stayed in.

This action created, in a sense, artificial gravity.

It’s called centrifugal force and it can simulate gravity.

In the context of a rotating space station, the normal force is directed outward and keeps the feet of an astronaut firmly planted away from the center.

The same thing happens when you spin a bucket full of water and it stays inside as it’s pushed back.

Being able to simulate gravity in space could help future astronauts that go to the moon and Mars.

“One of the constant challenges with living and working in space is reduced gravity,” Christopher Baker, NASA’s program executive for Flight Opportunities, said in a press release. “Many systems designed for use on Earth simply do not work the same elsewhere.”

A lot of different tools we need for the Moon and Mars could benefit from testing in partial gravity, including technologies for how to mine and use resources and environmental control and life support systems, said Baker.

Having the ability to create gravity also offers health benefits.

A 300 million-mile mission to Mars would take about seven to nine months under present propulsion systems and this prolonged exposure to the microgravity environment of space would play havoc with the neurological and physiological functions of the human body.

“NASA has learned that without Earth’s gravity affecting the human body, weight-bearing bones lose on average 1% to 1.5% of mineral density per month during spaceflight,” NASA states in a paper. “After returning to Earth, bone loss might not be completely corrected by rehabilitation; however, their risk for fracture is not higher.”

Without a proper diet and exercise routine, astronauts also lose muscle mass in microgravity faster than they would on Earth, says NASA.

Moreover, fluids in the body shift upward to the head in microgravity, which may put pressure on the eyes and cause vision problems.

Artificial gravity only exists in fiction — so far

There are many references to using a rotational effect to simulate gravity in science fiction.

One of the most memorable and reasonably accurate was created in 1968, produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick – 2001: A Space Odyssey.

And the novel Ringworld featured a great rotating wheel creating a world-size environment with artificial gravity.

While fictional use of this technology is common, no one has achieved successful efforts in real life.

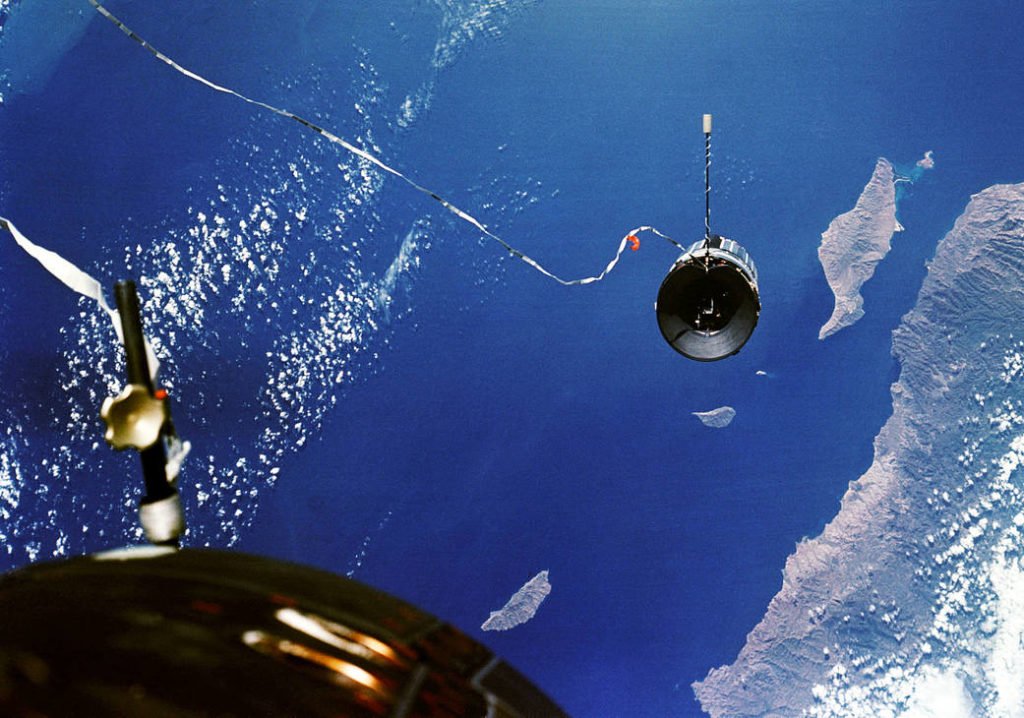

The Gemini XI mission experimented with rotational gravity back in 1966.

The Gemini XI spacecraft was tethered to a target vehicle. Gemini XI command pilot Charles Conrad and pilot Dick Gordon maneuvered their craft to keep the tether taut between the two.

They fired their side thrusters to slowly rotate the combined spacecraft, and they used centrifugal force to generate about 0.00015 g of artificial gravity.

Normal earth gravity is one g, so 0.00015 g isn’t much at all.

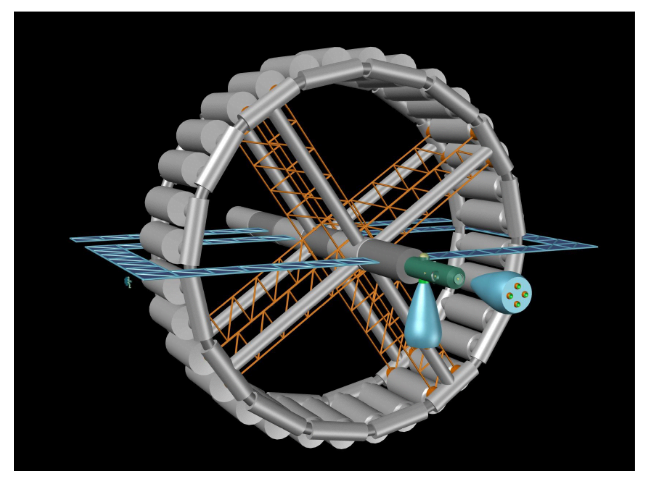

Werner Grandl, Clemens Böck, and others are researching the feasibility of adding spin to the next space station.

With the ISS expected to be decommissioned within the next five years, the Artificial Gravity Orbital Station is a proposed successor. The AGOS is modular and could be launched in stages using a SPACE-X Falcon to minimize costs, the researchers say.

Spinning around in circles may keep space travelers’ feet firmly planted on the floor but there are still many obstacles to be considered.

Space budgets are restrictive and agencies like NASA need to be careful about what large-scale projects they pursue.

Also, there are few launch vehicles that exist now or even in the next ten years that can actually put the station in orbit, according to the AGOS research.

If long spaceflights or prolonged stays in outer space environments are to be successful, simulated gravity will be needed to improve astronauts’ comfort and health.

Jim DeLillo writes about tech, science, and travel. He is also an adventure photographer specializing in transporting imagery and descriptive narrative. He lives in Cedarburg, WI with his wife, Judy. In addition to his work for MetaStellar, he also writes a weekly article for Telescope Live.