Morningside opened her eyes. She was in her bunk. Facing the polished steel wall. Wrapped in crisp, synthetic sheets that smelled of nothing.

She looked at her hand against the bottom sheet. Burnt-umber brown against clinical whiteness. She turned it over, exposing the lighter skin of her palm. Wiggled her fingers. The artificial gravity was behaving as expected.

She sat up. Her feet touched the silicone-coated floor, slightly warm to the touch.

Up was up. Down was down.

She stood steadily, without difficulty.

Dressing took no time at all—even lacing herself into magno-boots. Her fingers were well-rested. No swelling, no stiffness.

No breaks.

That stopped her. Why was that idea so strong in her head? That the last time she’d seen her hand it had been broken. Fingers non-operational. Struggling with—a closing hatch?

She shook her head, then caught sight of herself in the small mirror. Her hair was regulation close-cut. She touched a few remnant curls, smoothing them down. The hatch to her solitary quarters opened quietly, and she headed aft to the mess.

She was prepping a rousing valedictory in her head. Today was important. No more puddle-jump leaps from one planet to another. Today, they’d put Arjuna’s mad theory to the test, jumping between star systems. After so many others had failed, they’d be the success their planet needed. She was also rehearsing a few choice words for their success, historical words she’d speak back to Command. Something direct, simple, poetic. Something you could teach school children.

She paused outside the mess, smiling to herself, anticipating satisfaction, joy, on each of the crew’s so-different faces at that moment of success.

With a touch of the pressure plate, she opened the hatch.

And stopped smiling.

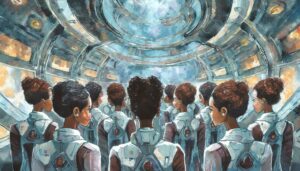

The mess was filled with herself. Thirty or forty duplicates of herself.

The versions of her reacted in disparate ways. Some kept eating their morning rations as if all that mattered was the food in front of them. Some were distracted by broken hands, head wounds. Others were helping with sterile wraps, sutures. One of her was curled up on the floor, in the right-hand corner, sobbing, while another stroked her back, murmuring comfort. A few looked up with the same raised eyebrow. Then, the one with the longest hair, grey, wooly dreadlocks, said to the others, “As you were, soldiers. It’s just another new one.”

Morningside stood, not in, not out, trying to make sense of the scene in front of her.

The older-her stood with a weary sigh, came across the room, and took Morningside’s arm in hers companionably.

“Let’s talk,” she said. “Come on. It’ll be quieter on the bridge.” This woman’s body was thicker than Morningside’s, slower. The woman walked exactly like Morningside’s auntie had, her mother’s sister, whose arthritis had made her so miserable.

Two other versions of her fell in on either side of them, a kind of guard. They were about the same age as Morningside, but it felt like they had more days under their belts. Each of their uniforms had alterations made to it, a sleeve removed, a stripe added. Their hair was longer, styled differently—twists on one, afro on the other. There was something in their eyes. Something shut-down. Some kind of pain.

As they guided her down the corridor, Morningside looked for signs of damage to the ship, but saw none. On the bridge, the screens showed no alarms. One of the guards pulled up the latest data from the internal and external ship monitors. Morningside moved forward to look closer.

That was it. The resonance drive was still running. Part of her relaxed—the test, it was all part of the test. The physics equivalent of hallucinations, that’s all these versions of herself were. She’d have to end the experiment from the inside. Or Command might end the experiment from the outside. Or the experiment might end itself—didn’t it have an internal timer? Though how did that work if this interstitial space had no linear time?

“Do you see now, Zero?” said the older one.

“Zero?” said Morningside sharply.

“I always call you new ones Captain Zero at first.”

“That’s lovely.” Morningside could afford sarcasm. She was only talking to herself, after all.

“You’re thinking it’s a sign of disrespect. It’s not—it’s descriptive. You’re the starting point. You’re the blank template from which all of me springs.”

“I’m not a blank,” Morningside said defensively, not entirely sure what she was defending against.

“No. But we’re all elaborations on you. I’m you. They’re you. We’re all you. I know it doesn’t make any sense right now.”

“But it will?” She didn’t trust this older version of herself. “If I’m Zero, what do I call you?”

“I call me Alpha.”

Of course, her bossy side would have taken the lead. “Not Captain Alpha?”

A micro-expression crossed the older woman’s face. Anger? Shame? “No. Alpha.”

“Well, Alpha, what’s happening here?”

Alpha gestured to the consoles. “You’ve seen.”

“The resonance drive,” said Morningside. “It’s still on.”

“Yes.”

“Diagnostics?”

“You’ve seen.”

The monitors reported emptiness around the ship. A vacuum, lightless, energyless. An interim state meant to last a split-second if Arjuna’s projections held true. Once you were in, there were no stars to guide by, no way of steering, no way of changing the calculations that cycled through the drive.

“Have you tried turning it off?” said Morningside.

The duplicates met each other’s eyes and laughed, the same small, chagrined laugh times three. How many times had she been through this? Was this always the first question she asked?

“Yes,” answered Alpha. “More than one of me has. I put a stop to that.”

“Why?”

“Because it always tears the ship apart.”

Morningside gestured to the ship around her. “But it’s whole now?”

“Yes. It comes back when it’s destroyed. Again and again. The first time, I admit I was grateful. I thought it was over. I was free.” Alpha shook her head, almost nostalgically. “But then I woke up. In my bunk. Alone. Reset at zero—except for the memories.”

Morningside thought of her hand. That broken hand, overlaid like a projected image.

“You’re remembering something,” said Alpha.

“Yes. But what?”

“It differs each time. How much I remember. Sometimes, death hasn’t erased a thing.”

“Do you mean we share somehow? One set of memories?”

“Only up to a point. From that point, each of me is distinct. But still me.”

Then I’m private in my own head, thought Morningside. Good to know.

She looked at the other women, quietly watching her. What thoughts were they keeping to themselves in the safety of their own heads?

“Where’s my crew? Don’t they come back?”

“No. They took the escape pods.”

Morningside felt relief, but made herself temper it. “Did they make it? Did they escape?”

“I haven’t heard otherwise, so I’ve decided to hope for the best.”

“What do you mean you haven’t heard otherwise?”

“There are no inbound communications.”

“What about outbound?” asked Morningside. “Have you tried a distress signal?”

“Yes,” said Alpha. “It’s always something I try. But how would Command intervene, do you think? In the middle of an experiment failing so spectacularly. Would they try to slow the ship? Board it? If there’s even a physical ship to be boarded any more.”

Morningside’s mind raced. “But the laws of physics—they’re still in operation. We have gravity, life support, power circulating to the drive.”

“Yes. It’s all very expected. Minus the separate conversations I’m having with myself all over the ship.”

Morningside found herself staring at the old woman’s eyes in a moment of opia. Who knew my eyelashes would turn out so grey?

She came back to herself. “Why is that? How does this even work?”

“I don’t know. One of me just shows up. Sometimes one of me just disappears.”

“There’s no logic to it?”

“No.”

Morningside couldn’t take it—the calmness in the woman’s voice. “Have you at least monitored the resonance cycles? How do you know it doesn’t hiccup one of us out on a specific oscillation? Your hair is grey and down to your butt, lady. How many years have you been sitting here not figuring anything out?”

Alpha laughed, but Morningside felt anger there. Or was she projecting onto this woman what she’d be feeling in her place?

“I figured out how to stay alive,” said Alpha, “so you’ll forgive me if that’s what I’ve focused on.”

“It took figuring out, did it?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

Alpha tilted her head. “Accidents. Negligence. Well-intentioned efforts to change the circumstances. You’ll find out soon enough.”

“Will I?” said Morningside. She couldn’t imagine it. This resignation. This acceptance.

“Yes. You will.” Alpha paused for emphasis. Finally, she said, “In the meantime, I have rules. I don’t turn off or damage the drive. I don’t trigger the distress signal. With the crew gone, I take shifts maintaining the vessel. Cleaning duties and mess prep are shared. A few of me have taken engineering duties, keeping the systems running smoothly. I’ve learned medicine as needed, and mechanical and electrical repair.” She stepped closer to Morningside. She smelled both familiar and strange. Her body heat radiated warmly against Morningside’s skin. Quietly, pointedly, she said, “Your military skills are no longer needed. You will find something useful to do, something necessary, something that suits you. I could have been many things in many universes. Now I have the opportunity to be them.”

She seemed to be waiting for that to sink in, so Morningside nodded in acknowledgment.

“With that, I would like to return to my breakfast.”

Morningside held up a hand. “I’d like to stay here. Go through the data.”

Alpha shook her head. “Time enough for that later. It doesn’t change. It never shows anything new.” She turned and started her slow, uneven walk off the bridge. The guards lingered, waiting. Morningside looked from one to the other.

“Am I always this stubborn?” she said. They smiled, a bit sympathetically she thought. But they stayed where they were, waiting for her. “Guess I’ll get some grub, like the woman says.”

As they returned to the mess, they passed more versions of her, heading back along the corridor, disappearing through the hatches to the crew quarters. Morningside was amazed at the variety of hairstyles and uniform alterations she saw. Some of them had even drawn patterns on their skin using what little make-up Morningside ever traveled with, her red lipstick. Every one, trying to mark themselves as separate. But all so obedient, so docile. Here she was, Captain Zero, already chafing, already feeling revolutionary.

In the mess, one guard walked her to a spare seat on a bench, and the other fetched her a bowl of hydrated rations and a spoon. They left, then, heading back to whichever table they belonged to. Morningside made friendly eye contact with the women seated at her table. Two of them acknowledged her presence with a nod or polite smile; one ignored her and kept eating. Morningside stirred the spoon through the gruel and wracked her brain for next steps.

The Lorelei was an old freighter ship that had been retrofitted for the experiment. Command had stocked it for a number of outcomes. Ideally, the experiment would result in a jump both to and from the intended long-distance target, but if the shiny, new resonance drive was only good one way, she was supplied for a long trip back to communication range on traditional engines. Her tail was mostly thrusters. Her gut was full of engines. The hollow cavity of her nose housed the bridge, sleeping quarters, and the aft mess. In the storage hold below were a certain amount of hard rations, water, waste recycling, traditional fuel reserves, various replacement parts so the ship could be maintained along the way.

Originally designed to be operated by a crew of 80, the ship had been staffed with only five for the experiment. Lucille Morningside, captain and communications officer. Eder Galdames, navigator and traditional engineer. Abhiroop Kaur, medical doctor and habitat engineer. And the two scientists who’d worked on the drive construction project, Chikere Onireti and Ly Minh Thuy, there to observe the results of the experimental leap, but also to operate the drive and navigate the ship while under its power.

There wasn’t much time for training together as a team before setting out, but Command screened them all to be psychologically compatible. They’d grown surprisingly close during the short test jumps. They weren’t intimate friends, but they were colleagues. A good solid crew. Unified in purpose.

Morningside wasn’t captain because of any science expertise. She needed Galdames to tell her the state of the traditional engines, and Ly and Onireti to interpret the output of the resonance drive. She was captain because she knew what questions to ask, when. She knew how to get people to trust her, trust each other, trust themselves. She knew how to build a team.

She looked around at her duplicates. That was the key, what she could do here. Bring together a team of herself. From those who’d had time to gain the expertise she needed, she could get either confirmation or contradiction of what Alpha had said. She could get access to the raw data from the drive and someone to interpret it for her, instead of relying on the heuristic programs that could, for all she knew, be rigged.

She would have to befriend the endless iterations of herself.

She’d start with her immediate neighbor on the bench. A duplicate with perhaps two years of hair, box braids tied up with a kerchief. That look wasn’t regulation, but of course no one was enforcing regulation any more.

“Hey,” she said with fake cheer. “Apparently, I’m Zero. What do they call you?”

The woman had smiled politely earlier, but now she had doubt in her eyes, studying Morningside a moment before she said, “They call me Sister.”

“What’s the history on that one?”

“I still think there’s some purpose to all this, some point. I’m not saying I believe in a higher power, but that’s how the others hear it. They laugh and ask me to pass the collection plate.”

“You saying you’re not religious?”

“Are you?” Sister asked. “I mean, is that somewhere in you?”

“No,” said Morningside, genuinely smiling, “not really.”

“There’s your answer.” Sister returned to her food.

Morningside said in a lower voice, less likely to be overheard. “Do you believe—all this?”

“All this?” said Sister, responding in an equally quiet voice. “Do I believe it’s happening? Yes, I have to. No, it’s impossible. Yes, it’s my reality. No, it’s some nightmare I’m going to wake up from. It’s all that.”

“And Alpha?”

Sister hesitated, her face guarded. “What about her?”

“Do you believe her? Her version of what’s happening?” Morningside hoped it wasn’t too soon for that question, but she found her impatience catching her up.

Sister paused before replying. “That’s a choice we all have to make. For better or worse. Some of us believe her, and it gives us peace. We’re doing the best we can until Command intervenes. Some of us believe her, and it drives us mad. We retreat to our quarters and scream at the walls. Which isn’t that different from those of us who don’t believe her. Except that group—the nonbelievers—they test, they try things.” Sister swallowed the last of her gruel, then set her spoon on the table. “Are you going to try something?”

Morningside shrugged, aiming for noncommittal.

Sister put her hand on Morningside’s hand. There was an odd frisson when her skin made contact with Morningside’s. Not static electricity. A faint, almost undetectable vibration.

“Don’t,” Sister said. She stood, picking up her bowl. Morningside watched her carry it to the disposal, noticing as she did that their table had emptied out. The mess had cleared, and Alpha was standing behind her.

“Have you gotten enough to eat?” said Alpha.

Morningside twisted around to face her. The guards were back, standing on either side. “Yes.”

“Then I’d like to recommend that you retire to your quarters. You can have the captain’s quarters as long as you wish. I’ve found that when I’m new, I need some time and quiet—to adjust to this new environment. I know you have more questions, but you’ll be better able to deal with things if you can let it all sink in.”

“You’re sending me to my room?” Morningside hit her with one of her biggest wise-ass smiles.

Alpha returned the smile, though with, Morningside couldn’t help thinking, a quality of mockery. “I am.”

Morningside stood and stepped over the bench. She sent one last studying look at Alpha, who did not flinch at the scrutiny. Then she allowed the guards to walk her to her quarters.

The hatch shut behind her. The room she’d left such a short time ago looked inappropriately normal.

She moved to the console at her desk. When she tried to log in, the computer rejected her authorization code. She’d have changed that first thing, too, if she’d been Alpha.

What now?

Her mind suggested all the possibilities: She wanted more information, now, without delay. She wanted to play it safe and wait and see what happened next. She wanted access to the com systems to confirm the ship’s isolation. She wanted to scream until she was hoarse. She wanted access to the resonance drive, even though she couldn’t interpret its output. Was shutting it down the only possible choice, the only way to find out if she really was trapped or if Alpha lied? She missed her crew. She longed after them with a kind of sickening desperation. She needed to make new allies, then, but her attempts with Sister had not been promising. Did she, instead, need to figure out the weaknesses of this strange solipsism of a society and pull until it unraveled? What then? She wanted to weep the way she had when she was a girl—some part of her was already weeping. Some exhausted part of her heard that weeping, and all she wanted was to lie down on that bed and give up.

That thought decided her. She didn’t give up. That wasn’t something she did.

The acceptable options started with getting out of this room.

Were the guards posted outside her door? Only one way to find out. She tried the hatch.

The magno-lock was on.

She looked up at the atmos-vent in the ceiling. Hardly big enough to fit her arm in, let alone to crawl to freedom through.

That left the hatch as the only exit.

But first she needed to blend in once she got out there. She pulled her uniform off and laid it on the bed. She attacked the seams at the shoulders and removed both sleeves. She put it back on and decided to roll each leg up to a different length. She looked at herself in the mirror—what little hair she had needed to look like more. The curls she patted down earlier, she encouraged to spring up. The final touch was to draw a lipstick spiral on one cheek.

A better scientist than she could have whipped up some way to reverse the lock—an electrical shock at the right location—but as a non-scientist she had a single choice, brute strength. She knew it was possible to force the locked hatch open. That’d been part of emergency training, how to extricate yourself in case of lock malfunction. She even knew what to use as a lever. The support leg from the bedside table, currently folded flat against the wall. She opened the table up and kicked the leg at its weakest point until she had the shiny chrome pipe free in her hands.

She set the pipe against the fulcrum of the hatch frame and turned her boots on, anchoring herself to the floor. Then she pushed with all the might in her well-kept body.

At first, there was no effect, but then she felt the smallest of shifts. She pushed harder, even added a grunt.

Sweat broke out all over her body as she breathed through the strain.

Another shift, bigger this time. A gap opening between the hatch and the frame.

But then her sweaty hands slipped on the pipe, and she crashed towards the door. Reflexively, her hand went toward the gap between the hatch and the frame, to trigger the hatch’s automatic opening mechanism. She could catch it, just—she stopped herself, twisting away, as the hatch snapped closed.

Broken fingers. A hatch. That must have been how it happened before.

The pipe fell soundlessly against the silicone flooring.

I get it, she thought, leaning against the frame. Sometimes, I don’t even get out of this room. But not today. Today I get out.

She dried her sweaty hands on the bedding, then sprayed them with antiperspirant. When she picked up the pipe, her hands no longer slid. She locked her boots again to the floor in front of the hatch, took a couple of deep breaths, set the pipe in place, and pushed.

This time, when the gap opened, she slid the pipe further in, shifting the fulcrum to the hatch itself. She struggled against the lever, weakening the magnetic field millimeter by millimeter, until the lock gave, and the hatch slid open the rest of the way.

She held the pipe high, swiveled from one side to another—no guards. She looked fore and aft along the corridor. Empty. But then voices coming from the forward end.

She couldn’t retreat. The open hatch was a giveaway, and she sure as hell wasn’t closing it just to go through that again.

As soundlessly as possible, still holding the pipe, she ran aft, hoping no hatches opened along the way to let any duplicates out.

At the hatch to the lower deck, she stuck the pipe under one arm and swung herself onto the descending metal ladder. As the hatch closed above her, she stopped, staring at her hands on the metal rung. It wasn’t one set of hands, but many. Overlaid again and again by echoes. How many times had she climbed down this ladder since the experiment began? Was she here again because some previous attempt had failed—or because it had succeeded? Was this overlap of memory a warning to turn back or a signal to continue? Gonna drive yourself crazy thinking like that. She closed her eyes and kept them closed to finish the descent.

The high, arched space of the lower deck was filled with the bass churn of the traditional engines, running at their lowest capacity, generating no propulsive power, only enough electrical power to charge the resonance drive. The sharp stink of the burning fuel stung her nose and her eyes. She scanned the room for any movement, any versions of herself, but she was alone. She sought out the resonance drive at the heart of the engine room, nestled between the traditional engines. The resonance drive made no noise. All of its powers of propulsion, all its spacetime-bending, were silent powers. The lights in the drive room reflected off the shining copper exterior of it, bouncing highlights off onto the brushed-steel ceiling and walls.

She remembered Alpha’s voice: I don’t turn off or damage the drive.

You do today, sunshine.

She looked closer. The drive’s manual override had been removed entirely, and its protective casing had been sealed shut with a laser solder. The case could withstand anything in the engine room, anything on the ship. Morningside was tempted to hit it a few times with the pipe for good measure anyway.

Could she cut off the energy supply to the drive? She examined the traditional engines, but they were equally sealed off.

She looked at her reflection in the protective casing. Damn, it’s hard to outwit yourself.

Next option: distress call. She could have activated it from any console if she weren’t locked out, so that left only the manual activation point on the bridge. A good old-fashioned switch. That was her next destination. Though Alpha had likely anticipated her there, too.

What she needed was a distraction. Something to draw Alpha and the others away from the bridge.

In the storage hold, she found supplies—flammable materials to pile at the base of the resonance drive, a small container’s worth of traditional fuel siphoned from the backup tank, the battery from a piece of hand-held survey equipment. She smashed the battery with the pipe until it started sparking, then kicked it into the fuel-soaked supplies. She paused long enough to see the fuel combust, then ran for the starboard ladder. She climbed as quickly as she could, pipe under one arm, coughing as the fetid smoke rose around her.

At the top, she exited the hatch, then jammed the pipe into the track to keep it open. The roar of the traditional engines filled the corridor. She could barely hear the impact of her boot against the pipe as she kicked it into place. When it was stuck for sure, she cried out, “Fire!” in both directions and ran to the next nearest hatch.

Crew quarters. The hatch slid closed behind her, sealing off the noise of the corridor.

She wasn’t alone. A duplicate was sitting on the floor, her back against a wall. She was out of uniform, in her skivvies, goosebumps raised on ashy arms and legs. She seemed unhurt, but she was collapsed against the wall as if she had no energy left to move.

“No need to worry about me,” the woman said.

Morningside couldn’t help it—she asked, “Are you okay?”

That other-her smiled weakly. “Of course not. Nice of you to ask, though.” She shivered, pulling her knees closer to her. “Don’t tell the others you saw me like this.”

“I won’t.”

“Thank you.” The woman leaned her head back and closed her eyes, her teeth starting to chatter.

Morningside re-opened the hatch, this time to chaos. Versions of her were swarming, some still arriving, some disappearing down the ladder. The foul smoke had risen out through the open hatch and crept along the corridor’s ceiling. Duplicates were chattering, coughing, yelling in panic. A space cleared among them, and Alpha and her guards stepped through.

Alpha shouted to the others, “You have nothing to add here. Back to your quarters.” She directed the guards down the ladder, then stayed, looking down through the open hatch into the acrid haze.

Some duplicates listened to Alpha and began to disperse along the corridors. Others remained, though they crowded less towards the open hatch, giving Alpha a wide berth.

Morningside fell in with those who were leaving. Her eyes seeped from the smoke. She kept to the outer curve of the corridor, head down, mouth and nose covered with her arm, counting the hatches to determine her progress.

There’d been more quarters than crew when she’d started this journey. Four bunks per hatch. Ten hatches starboard, ten portside. How many of those bunks were filled now? One of her to sleep in every bed.

Near the bridge, the atmos-scrubbers worked to clean the air, so she could breathe enough to move faster. On the empty bridge, she made for the communications array. Crouched, she slid back the emergency beacon’s cover where it was set almost invisibly beneath the primary instrument panel. She had only to press her fingers and—

“No,” she heard someone with her own voice say. “We do not sing today.”

Metal pipe cracked against the back of her skull, and she fell into darkness.

When Morningside opened her eyes, she was lying heavily on the floor, her head resting in Sister’s lap. Her head hurt. So much. Her vision was blurred, but she saw that Alpha knelt beside her, still holding the pipe she’d used to hit her.

A few minutes passed, filled only with the sounds of Morningside’s ragged breaths, the breath of the woman holding her, the breath of the woman kneeling beside her.

Finally, Morningside said, “What really happened to my crew?”

Alpha set down the pipe and took her hand, so lovingly that Morningside felt disgust. “I freed them, of course. Well, Chikere and I did. Yes, in the end I got to call him Chikere, and he called me Lucie. When all hell had broken loose, it didn’t seem to matter what bonds we had in the outside world. Not his wife or his children. Though I think that contributed to the end, of course. When he finally realized he wasn’t going to see them again. When he realized he wasn’t enduring this hell for their sakes.

“You understand, we were trapped. In this ship, under impossible circumstances. We tried turning off the drive, modifying it, rewriting its equations. But anything like that was pointless. Each time, we had to start over, sometimes remembering, sometimes not, sometimes repeating, sometimes not. We had no connection to linear time. All our lives overlapped. Trying to live like that—multiple, simultaneous, futile, hopeless—it broke us all to varying degrees. It became clear that the things we thought mattered didn’t—not military order or law or conscience. There simply was no reason to hold back any impulse. At first, that meant all the quiet, subterranean attractions we felt for each other were expressed. It meant adultery and love triangles and unending arguments. But next came rape and killing and torture. Amazing the things you’ll do when the person you’re doing them to simply shows up the next cycle, unharmed, perhaps not even remembering what happened. Or they might remember, which meant rounds of retribution. Killing the one who killed you. Killing the ones they cared about. People tried to build fortresses to protect themselves, set elaborate traps. You’d walk into a room, trip a wire, and be dead in a moment, pierced through with shrapnel.”

Alpha seemed to see something, then, in Morningside’s eyes. She leaned her face closer, so much closer. “Did you believe,” she said, “that we were better than that? With only infinity before us and no escape? You won’t believe, but Abhiroop was one of the worst. Yes, Kaur, the peacemaker, who got along with everyone. But once she’d been killed enough times—tortured enough times, raped enough times—she would simply kill you in a moment. She’d get tired of what you were saying—or get scared—and she’d drive her kirpan into your throat. Quick in and out. And wipe it off on her uniform.”

Morningside couldn’t help but flinch. Alpha did not seem horrified by what she was saying.

“But you want to know what happened to them in the end. Why they’re not here, repeating. Chikere figured it out. With his calculations, we could boost the velocity of the escape pods enough to throw them outside the drive’s sphere of influence. It was theoretical, at first, but he put Galdames in one, and when his duplicates had died out, he never came back. The rest of us thought he was hiding out somewhere, Galdames, who knew the ship so well, but Chikere knew he was gone. He told me what he’d done. What it meant. For all of us. Release. So we talked the others into the pods. We lied to Abhiroop. We told her we’d discovered a way home. She chose to believe us, and let us kill all versions of her but the one we sent. Ly, of course, we had to tell the truth. She was as brilliant as Chikere, if not more, and she knew the improbabilities. She argued with her selves before they agreed which one of them would go. But once they had decided, all but the chosen one poisoned themselves with fuel waste. That last Ly was grateful, so grateful, as we sealed her in.

“Then it came time for Chikere. He kissed me good-bye, held me one last time, then he was gone. We talked about what he would do if it did mean escape—if he did make it to the universe we’d left behind. Who knew what was happening in that real universe? Either no time could have passed or an eon. Perhaps Command would be there, still monitoring, and they’d pick him up right away. Or perhaps he was ejecting himself into empty space, a universe where our people had gone extinct along with our star, or had succeeded and traveled on to other star systems, other galaxies even. There could be no one in range to communicate with. He could float in that escape pod until the life support ran out. Then it would be his coffin. We didn’t know. But he was so tired. He was so—tired.”

Morningside wished she had enough strength left to pull her hand away from Alpha. She didn’t want to be touched by her. She didn’t want that contamination against her skin.

She whispered, her throat thick. “Why didn’t you go with him?”

Alpha smiled, such a glorious brilliant smile, the full whiteness of her teeth against the dark brown skin. “Ah, my sweet child. The captain always goes down with her ship.”

Morningside wished she believed that, that she’d stayed on the ship for the right reasons, for noble reasons. But she knew her own instinct to survive was too much. She knew she couldn’t do it. Couldn’t get herself into that pod. She was willing to tolerate all this, alone or populous, to stay alive. Morningside felt the tears trailing down her temples, into her hair. So cool against her skin. She looked up into Sister’s eyes. Could the woman still have optimism after this? Could she still believe in a larger benevolence after all this?

“We only have her word,” Morningside whispered. “That this is what happened. It might be lies, what she’s telling us. Lies.”

“I know,” said Sister. “I know.” She touched her fingers gently to Morningside’s forehead, a sweet, soft touch.

Morningside blinked sluggishly. “Then do something about it. Do something.”

“Some day I will,” Sister said. “When it’s right. When there’s a sign.”

“A sign. What more do you need? I’m dying,” said Morningside. “I’m dying for this, and you can’t even—”

Sister never heard the end of Zero’s sentence. The woman died. This was the first time it had happened like this—for Sister, at least. She’d seen other versions of herself die in various ways, but it was different to hold the dead weight of herself, to feel herself turn from animate to inanimate. To feel herself stop.

The last tears dried in Zero’s eyes. Her corneas grew dull like chalk.

Around her, Sister heard the others talking—a few jabs of black humor, get a hold of yourself, such a close call, what should we do with the body? Alpha answering: Put it in the bio-recycling. I don’t want it to smell.

Sister thought of herself as an agnostic. She didn’t have faith—she was just unwilling to discount the possibility of meaning, of consequence, of patterns that made sense. The other Morningsides accused her of full-blown religion, but that wasn’t her at all. She was just trying to sift through the impossible seduction and brutality of it all, and not give up on some way through, some way out.

She lowered Zero’s body to the floor. Others came forward to take it. She stood, as they each grabbed a limb and heaved upwards. She stepped back and watched four women, who were the same woman, bearing the ruined body of that same woman away.

What way is there to explain what she felt as she watched? What odd chaos of grief and rage? What confusion of love and hope? Too much.

With a terrible cry, Sister turned to the panel behind her and triggered the distress call before they could kill her too.

This story previously appeared in Teleport Magazine, November 2021.

Edited by Marie Ginga

Sian M. Jones received an MFA in fiction from Mills College. Her work has appeared in Quail Bell Magazine and Doubleback Review, among other publications. In her day job, she writes as clearly as she can about complex code. She occasionally updates her website jonessian.