“Tobias,” my dear friend Loosestrife said to me one afternoon as I perched on his drawing-room mantelpiece contentedly smoking my pipe. “I have, of late, as you well know, gone up in the world. My investments are yielding excellent returns, the cloud-mining venture alone has brought me enough wealth to build this magnificent stately brugh, and my trousers have never been finer–look you here at these new breeches that I purchased only yesterday at Honeysuckle and Garlic’s.” I peered over the bowl of my pipe to appraise them. “Do you remember that particularly clear evening back in June? Well sir, these breeches are sewn with the starlight from that very night! Mr. Honeysuckle assures me that they are the finest he has ever made, and therefore, it follows that they must be the finest that you–or indeed anyone–has ever seen.”

I do not, as a rule, encourage Loosestrife with too many compliments–he is quite self-assured enough as it is. But I did have to admit that they were indeed a magnificent pair of trousers.

“I have a brugh to rival anything within a thousand leagues – even Baron Vetchling’s Citadel of Midnight pales in comparison to my abode, fine clothes, and even a friend who rides my coattails–everything a man of station is meant to have.”

I balked a little at the last remark, but my face was sufficiently obscured by my pipe, allowing Loosestrife to continue unhindered.

“The one thing I lack,” he said, assuming a pose that accentuated his trousers to their fullest glory, “the one thing that will secure my position for good, is a servant–a human servant!”

My response to this particular remark was far less easy to obscure and resulted in the spilling of hot tobacco (in no trivial amount) onto my second-best smoking jacket.

“Why, my dear Loosestrife!” I cried, hastily brushing the tobacco away. “The last human servant in Faerie died a decade ago, and you know as well as I do that the paths between their world and ours have been sealed since the debacle at Cottingley.”

“Then how, if I do not have a human servant, am I to show myself of equal station with all the barons, earls, marquesses, viscounts, and dukes of Faerie, when even a lowly squire was expected to have at the very least a basic serving staff of changelings?”

“Times change, dear friend,” I said, giving my pipe a philosophical series of puffs. “I’d put it out of mind if I were you.”

But my friend would not–indeed, could not–put it out of mind. He thought about the problem night and day. He dreamed of it when he should have been dreaming of more genial things–dawnlight-trimmed jerkins or suits of the finest gossamer or obtaining a more articulate horse, to name a few. He pondered over the problem at breakfast, leaving his honeycomb all but untouched; he hardly danced at all at parties, preferring to mope pensively in corners; and he was constantly distracted at the gaming table, a state of mind that caused him and his unlucky partner (yours truly) to lose a not insubstantial sum (as well as nearly several limbs) to some very unforgiving gentlemen of the trollish persuasion.

One day, however, when I was again installed on his drawing-room mantelpiece and enjoying immensely the pleasures of my pipe, Loosestrife exclaimed “Ah-ha! I have it!” so loudly that I almost set myself ablaze.

“What do you have, sir,” I shouted, “that has almost burned me to a cinder!”

“The answer to my servant problem!” he cried.

I listened as intently as a man who has twice only narrowly escaped ruining his second-best smoking jacket could, before replying that, though I was sure the plan would have some amusing results, I thought it follysome and best left unrealised. Loosestrife replied that my lack of encouragement was making his ears ring, and I should either desist or find another house in which to smoke my pipe.

✸✸✸

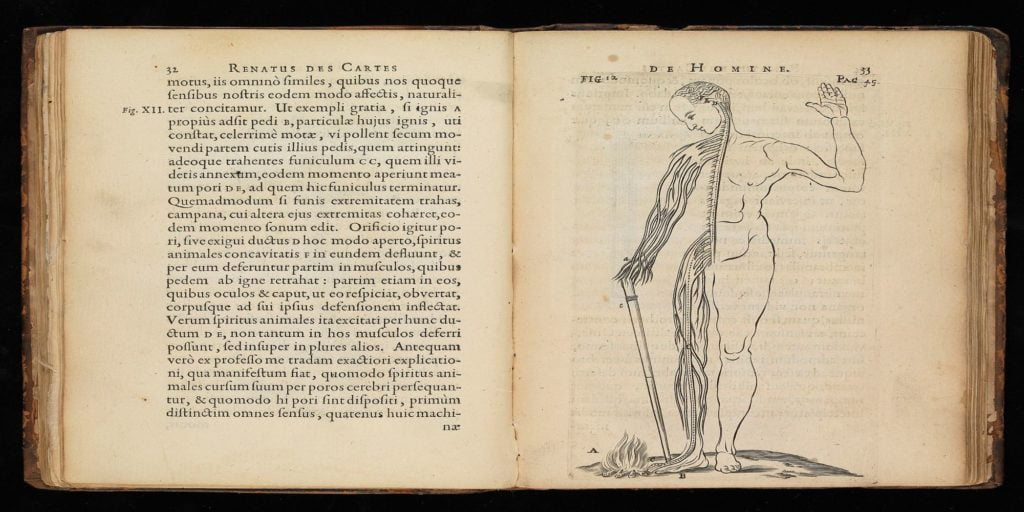

“This,” Loosestrife explained to me, several days later while pointing to an illustration in an ungainly, leather-bound tome that he had bought at some cost from the septennial market at Fool’s Errand, “is what the anatomists call the sceletus. I believe I have made a fair representation of it out of these twigs and branches, do you not think?”

“Indeed,” I replied, “though the artist seems to have omitted this nest of song thrushes in his representation.”

Loosestrife waved my objection away. “Details, Tobias. Mere details.”

“And for the head I see you have procured one of Widow Darkrain’s turnips.”

“Not just any turnip, my friend. This turnip has won first prize at the Lammas fair three hundred years in a row. It cost me a pretty penny, I can tell you. And as you can see, I have carved all the requisite holes for the various sensory organs.”

“And what about the musculi, and the arteriae?” I asked, flipping now myself through the book.

“A good question, my dear Tobias,” he said. “For the musculi, I have these mice, freshly collected from the pantry, and for the arteriae, I have used a mixture of ivy from the front of the brugh, while for the finer vessels, these bulrushes from the stream at the bottom of the garden.”

“And the skin . . . the cutis?”

“Offa’s Dyke! I had not thought of it. What does human skin look like?”

“Well, it is all wrinkled and grey, like an old pear, or a walnut,” I answered. “Or so I remember being the case when last I saw a changeling servant at one of Tom Thistletop’s solstice soirees.”

Loosestrife raised the more hirsute of his eyebrows. “Very well,” I said, unable to suffer such bushy disbelief, “or so I have been told by people who attended Tom Thistletop’s soirees. In any case, I’ve been told their skin has a distinct droopiness about it and is mottled and veined like a well-aged cheese.”

“Cheese, you say?” Loosestrife now raised the lesser of his eyebrows, which, joining its brother high on my friend’s brow, transformed his expression to one of glee. “Now that is fortunate, as I just so happen to have a wheel of Old Cob Deadnettle’s cheese maturing in the dairy (from the time he insisted on going everywhere as a goat, remember?)”

He hurried off and in a moment came back with a great wheel of pungent blue cheese.

“Poof!” I cried, wondering what Old Cob Deadnettle must have been eating during his time as a goat. “Yes, that’s the type of thing.”

Several minutes and much smeared cheese later, we surveyed the creature. “A fine specimen!” said Loosestrife, wiping the cheese from his hands.

“But it is completely immobile, my dear Loosestrife,” I observed. “It lies there like a dead toad! How is it to perform its duties in this state?”

“You are right, Tobias,” he replied. “We must animate it with what humans call a soul! An anima! How shall we do it, do you think?”

“Does this book of anatomy not mention where one can find a soul?”

“No, it is all joints and vertebrae and cartilages–it makes no mention of souls. Indeed it is quite dull and, if I may say, painfully lacking in anything ineffable.”

It was now my turn to have a moment of enlightenment. “My dear Loosestrife,” I cried, “I think I have it. Humans are known for prizing reason above all things, are they not?” He nodded most vehemently. “Then let us imbue this creature with reason!”

“Well said, my friend! But where to get this reason that the humans possess in droves? I see very little of it around here. Indeed it strikes me that in Faerie it is practically nonexistent!”

“I have the answer to that too.”

“You do?”

“Yes, indeed! Books!”

“Books?”

“Books are where humans get their reason–all their strange ideas and punctilious sciences, their anatomy and philosophy, and empirical geography–books!”

“But where shall we find such books? No respectable Faerie would have such drivel in his library. Why, my library practically overflows with grimoires, gramaryes, and cantripædiæ. But the books you speak of? Not one, sir!”

I pondered for a moment, taking several puffs of my pipe. Eventually I said:

“The fairer sex are known to dally in reasonable things, are they not? I know a lady who delights in all things reason and logic. Quite a splendid creature, though she does tend to be a little too levelheaded at times.”

“Her name?”

“Miss Marjory Greenteeth who lives over the hill at Wit’s End. She, I know, has a large collection of thoroughly pragmatic books.”

“Then let us visit her at once!” my friend exclaimed. “There is not a moment to lose!”

✸✸✸

Marjory Greenteeth lived in a large, once-grand château of moss-covered stone at the rear of a windswept estate overgrown with thin, dreary hawthorn trees.

“Good grief,” said Loosestrife. “What a terribly humdrum place.”

“I assure you, Loosestrife,” I said, “that the Greenteeths are a family of the highest breeding, though one admits that they have perhaps fallen on rather difficult times of late.”

Loosestrife acknowledged this with as much grace as a man who has recently gone up in the world could and proceeded to pull the tasselled bell cord that hung at the side of the somewhat haggard front entrance. Chimes rang within the château, peal after peal echoing through its many wings and galleries. After a moment, the door was opened by a portly man of gruff appearance with whiskers that reached most way to the ground (had the man been better dressed, one might have assumed that his beard was a modern fancy of the aristocracy; however, by the state of the house and the man’s poorly mended clothing, one could safely hazard that his bearded long-windedness was down to nothing more eccentric than an inability to afford a barber). It was also quite clear that this particular gentleman was trying, and failing, to conceal a small, though undoubtedly potent, cannonette behind his back.

“Good day, sirs. How may I be of service to you?” said the man, looking the two of us up and down. “You wouldn’t happen to be creditors, would you?”

“No, sir,” said Loosestrife. “My name is Loosestrife Foulweather and this is my companion, Tobias Tamlane. We are here to speak with Miss Marjory, your daughter.”

“Marjory, you say! And what, may I ask, do you want with her?”

“Why, sir, we merely wish to–”

“Don’t fancy marrying her, do you?”

“I beg your pardon, sir?” said Loosestrife.

“I said”–he raised his voice–“don’t fancy marrying her, do you?”

“Sir, I have not come here to marry your daughter, merely to borrow some of her books!”

“Pity, pity . . .” he said, his moustaches drooping. “Are you sure I can’t persuade you?”

I leaned over and whispered in Loosestrife’s ear: “He’ll never let us in at this rate! Agree to marry his daughter and be done with it.”

Loosestrife considered it and returned his gaze to Mr. Greenteeth. “I will consider the matter, sir. But I can do no more than that while standing here shivering on your doorstep.”

“Wonderful! Oh, Wonderful!” said Mr. Greenteeth. “Come in! Come in, do! I believe my little Marjory is in the library; allow me to escort you there at once!” With that, he led us through the many ill-lit corridors (ill-lit more from shame at the state of the wallpaper than a lack of candles, I’m sure–though I cannot imagine that candles would otherwise have been in abundance either) and up several dilapidated staircases that creaked and moaned and lowed as if there were a menagerie of broken-limbed creatures trapped below, and every step we took was agony to them.

As a man who had recently gone up in the world, my dear friend Loosestrife viewed the decrepitude with great interest. “I was under the impression, sir, that you had once been a man of great means and wealth.”

“You are quite right, Mr. Foulweather, you are right. My home was once a paragon amongst brughs, a paradise, with intricately woven carpets, ornate tapestries, brocaded sofas; commodes, armoires, and chiffoniers of ebony, walnut, and oak; glasses of crystal, services (both dinner and tea) of silver and gold–Oh! Mr. Foulweather, it would have melted your heart.”

“And human servants, I’d warrant, too?”

“Oh yes! Butlers, footmen, cooks, maids of almost every variety, ostlers, gardeners, hall boys–I had to part with them all, each and every one. All long dead now, though, of course. Now my house is served by nothing more than a troupe of diligent house spiders, who, in all fairness, do keep away the flies. Cobwebs and dust, sir! That is what decorates my brugh now.”

“But what happened, Mr. Greenteeth?” Loosestrife asked.

“Relatives!” came the grave reply. “Accursed relatives descending on us like rats! And dependents, and second cousins, and third cousins, and uncles and aunts, and many of them twice or three times removed! They ate and spent and borrowed me out of house and home, sir. Why, I had to sell everything to pay off my creditors.”

“Mr Greenteeth. I am most sympathetic,” said Loosestrife.

“Thank you, Mr. Foulweather. Your sympathies are kindly received. Now, if you could lighten my burden by taking my daughter as your bride, you would indeed be doing me a great service. I cannot promise much of a dowry, but if you truly desire the books that you wish to borrow, I may be able to make a permanent exception of them.”

Loosestrife considered this for a moment. He had not bargained on leaving Mr. Greenteeth’s house with a bride as well as books, but as he was going up in the world, he could not stay a bachelor forever–it simply wasn’t done. If he was to have a fashionable house with a fashionable servant and all manner of fashionable rooms and table settings and dinner sets and tea services and curtains made from expensive cloth, then it would only be fitting that he had a wife as well.

“Very well, sir,” he said at last. “I accept your offer with glee.”

“Wonderful! Wonderful! Ah, here is my rather modest library, and your new bride reclines within.”

Mr. Greenteeth opened the library door and stepped aside to let us enter.

On one of the room’s threadbare armchairs sat a pretty young woman with an enormous pouf of midnight-black hair that smouldered with the multicoloured iridescence of opals.

“May I help you?” said the lady.

“Good evening, Miss Greenteeth. My name is Loosestrife Foulweather and I am here to request some of your books and, it has recently been agreed, your hand in marriage.”

“Oh, erm, no thank you,” she said, and turned her head back to the book she was reading.

Loosestrife looked at Mr. Greenteeth, who shrugged and rolled his eyes, so he returned his gaze to the lady and once again cleared his throat. “Miss Greenteeth–Marjory–may I call you Marjory?”

Marjory ignored him.

“Marjory,” he continued regardless, “your father and I have come to an agreement that you should be my wife, and in return he will grant me permanent leave to borrow some of the books in your library. Is that not agreeable to you?”

“Not particularly.” said Marjory, not looking up from her book.

Loosestrife looked at Mr. Greenteeth again, who this time took the hint and piped up: “Marjory, dear, you must do as your father wills.”

“I will do no such thing,” said Marjory. “A woman should be able to choose whom she marries, if and when she sees fit to do so.”

“Oh, such reason! That’s what I get for allowing you to indulge yourself with all those dreary human books.”

“If I am to marry this comparative stranger, father dear, then there must be some advantage to it. As far as I see, my books are here; they are my pleasure, so here I shall remain.”

“Ah, but Marjory,” said Loosestrife. “I see you have a fondness for human books, yes?”

Marjory nodded, almost imperceptibly.

“You have a fondness for humans, then. But have you ever actually seen a human, Marjory?”

Marjory looked up briefly. “Only when I was a girl,” she said, and returned her gaze to her book. “Before father sold them all. I barely remember them.”

“Well, then. If you come with me, you shall see a real human servant. I have, you see, made quite some progress in constructing one myself. Would you like to see it?”

Marjory’s eyes did not leave her book, but she began to bite her lip, and a faint quiver could be detected in her lower jaw. After what she must have considered an adequate pause, Marjory raised her head and said:

“Very well, then, I do believe I should like to see that.”

✸✸✸

“Behold, my dear,” said Loosestrife when the formalities of marriage had been dealt with, and Marjory and her books had been installed in the house, “our human servant!”

“It doesn’t look very human,” said Marjory, looking at the strange and ungainly mass of lumps that lay on the tulipwood commode in Loosetrife’s back parlour.

“My dear, that is because you haven’t seen a human since you were a little girl. Your memory of them is rather fuzzy I imagine.”

“But I have seen illustrations,” she said.

“Pedantically accurate renderings no doubt, devoid of the most basic fanciful embellishments.”

Marjory gave a dissatisfied humph and began to prod at the lump of inanimate matter with an elegant finger.

“Now, now, my dear,” said Loosestrife. “Do you not have any wifely duties to perform? Making . . . erm . . . tea? . . . or darning something, perhaps?”

Never having had a wife before, my dear friend had little idea of what duties were expected of them.

“No,” came the curt reply, “I do not.”

Loosestrife began to protest, but Marjory continued: “What exactly are you going to do with my books?” she asked. “You can’t teach this lump to read, surely. It can’t even open its eyes.”

“We shall imbue him with an anima! Wife, fetch my cauldron!”

“Fetch it yourself.”

Loosestrife blanched. “. . . Very well.” He fetched the cauldron from its cupboard, placed it on a tripod so as to avoid scorching the carpet, and reluctant to risk asking any more of his wife, requested that I proceed with providing the heat–a task that I confess to thoroughly enjoying–whereby I commenced hurling my finest and most vehement insults at the pot until it very nearly boiled over with rage.

“Easy now, Tobias,” he said. “Perhaps you could temper your insults just a modicum, lest the sensitive fellow explode. There are also,” he added, “ladies present.” To which Marjory responded with an insult of her own that set the poor fellow’s ears smoking.

After he had doused them in cold water, and checked that my insults were keeping the pot at the optimum temperature, Loosestrife opened the great chest of books provided by Mr. Greenteeth and picked out a series of leather-bound tomes: “Aristotle’s Organon.” He nodded and dropped it into the cauldron. “Euclid’s Elements, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding by a Mr. John Locke, and–aha!–Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management, for, I think, practical purposes.”

The cauldron began to simmer gently. “Now, where is my distilling apparatus?” he said. “Excuse me, my dear, while I go look in the cellar.”

Loosestrife left the room once again, leaving Marjory and myself alone in the room. I, having effused enough foul language at the cauldron to keep it bubbling for several hours, and knowing full well that my capacity for small talk with young ladies is somewhat nonexistent, retreated to the mantelpiece above the small fireplace, where I soon fell into contemplation, cradling my pipe.

Marjory, on the other hand, looked altogether vexed. A frown had taken residence upon her forehead and lay there like a stubborn cat. “Why, you can’t have Locke without Hume, and what about Rousseau and Kant? They’ve been omitted altogether! And Mr. Spinoza too. And why Aristotle but no Plato? Euclid without Newton, too, is an omission.” She began to rummage around in the chest, pulling out book after book. “Oh! And here we have Paine, Hobbes, Montesquieu! They must all go in.”

When Loosestrife returned with his distilling apparatus, he found the chest all but empty.

“Dearest,” he said, with a forced smile, “where have all the books gone?”

“Oh, I added them to the mixture,” she said. “It’s far better this way.”

“I see,” replied Loosestrife, scratching his head. “I do fear, however, that this human will be too reasonable by far.” The viscous liquid in the pot belched as if in agreement. It had turned from a thin, watery yellow to a deep and profound gold.

“Oh, do stop being such a stuffy old bore!” said Marjory. “Where is your sense of adventure!”

“Here, here,” I said, not out of any particular desire for adventure, but it is always necessary for one’s opinion to be heard; it prevents one from being mistaken for a piece of furniture.

“Come now, Husband,” Marjory said, patting him on the shoulder tenderly. “Is the anima ready? It looks wonderful!”

Loosestrife did not quite know what had gone wrong. His new bride was far more involved than he’d imagined, and his human servant was soon to be a savant rather than a loyal worker. Indeed, he was rapidly learning that being married was a lot more trouble than he’d imagined. But he supposed it was simply the price of going up in the world.

“Well, my dear, it needs distilling, which will take a few hours. But, perhaps I can convince the apparatus to hurry the process along.”

“Would you, my love?” said Marjory. “It would please me ever so much.”

Loosestrife blushed. “Very well,” he said, and began to set up the copper still, bribing it with promises of honey brandy and dew liquor in the very near future. He decanted the liquid from the cauldron, which looked far more potent than he’d expected, into the flask, and in the blink of an eye, it had evaporated, condensed, and fallen, drop by golden drop, into the collection bottle.

Loosestrife took the bottle and proffered it: “Would you, my darling, care to do the honours?”

“Why, my dear friend, certainly!” I said, rising from my chair and tapping out my pipe (I believe, in hindsight, that I may have misread the situation).

“I think he means me, Tobias.”

“Madam,” I replied, not willing to be gotten the better of, “you may be Loosestrife’s wife, but I have been decorating his house for decades. This honour must surely go to me.”

We turned to Loosestrife, both of us with severely affronted faces.

But Loosestrife merely sighed, saying, “I do not like this going up in the world one bit.”

✸✸✸

Slowly the creature sat upright, its eyes shining with the lancing light of a summer dawn, which faded, soon enough, to the bright amber of sun-baked wheat. It coughed, emitting a twitter of birdsong as it did so, flexed its muscles with a squeak, and set its feet gingerly on the ground.

“Careful now, my dear Loosestrife,” I said, eyeing the creature with a mixture of suspicion and awe, “it may bite.”

“Nonsense!” he replied, and proceeded to clear his throat before addressing the creature in a loud and commanding voice: “Good morning, servant. My name is Loosestrife Foulweather, your master and, I flatter myself, your creator . . .” The creature blinked, but did not speak, unable, it seemed, to comprehend.

Marjory, without taking her eyes off the creature, leaned over to her husband. “Can it understand you? Why does it not speak?”

“Leave it to me, my dear,” he said, patting her on the shoulder. “It would do you good, man, to address the lady of the house and I as Master and Mistress. I am all for quiet servants, but a mute one who cannot even utter the most basic formalities is quite out of the question! Come now. Speak up.”

But the creature still did not answer. Instead, something behind Loosestrife was engaging its attention.

“What? What is it? Is there something behind me? Is Tobias doing something amusing behind my back?”

But the creature was not looking at me either, and after a moment, it pushed past all three of us and became very interested in Loosestrife’s walnut games table.

“What is it, man? Have you never seen a games table before?” said Loosestrife, wrinkling his brow in frustration.

I pointed out (with the utmost discretion, of course) that the creature had likely not seen a games table before, or indeed, any table, as it had but moments before come into animation.

“Yes, well–ahem–I suppose not. Now listen here–”

The human turned suddenly and looked at Loosestrife with its eyes of summer wheat and said with a twitter, “This is not right. This table has no legs! How is it standing? The laws of gravity clearly state that it should fall to the ground!”

Loosestrife pressed his hand to his forehead. “The table, you utterly reasonable human, stands on my orders. It needs no legs to do so.”

The human ran now to the walls. “And the walls, the cornices, the lintels, the door posts . . . they defy the geometry of Euclid!”

“The walls do as they’re told. I find them more aesthetically pleasing when they are thus contorted.”

“And this cauldron. It remains red-hot, with no source of heat? The laws of thermodynamics declare this to be impossible!”

“By oak and ash and thorn, I have never encountered anyone as frustratingly obtuse as you! The cauldron remains hot because Tobias here hurled enough insults at it to keep it fuming for several hours. Do you know nothing, man?”

“I know only reason, sir,” said the servant.

“Useless! Utterly useless!” he said, throwing up his hands. “He understands nothing, Tobias. Nothing! We shall have to destroy him and start again. Where’s my cheese knife?”

Marjory, however, would have none of it. “Husband,” she said, “if I may interject.”

Loosestrife was busy searching for his cheese knife, but he nodded that she should continue.

“If indeed this servant is to be but a symbol of your going up in the world, then surely it matters not that his domestic skills be lacking. Surely the more logical he is, the more impressive he will be to your guests. Why, you now own the most reasonable servant ever to serve in Faerie! Surely you wouldn’t want to hack at that accolade with your cheese knife!”

“Well, no, I suppose not. Yes . . . yes. Jolly good point, my dear. Obtuse! You shall remain in my service, for now at least. Perhaps there is something to be said for this reason of yours after all, my dear.”

✸✸✸

Over the next several days, owing most certainly to the presence of such a reasonable creature as Loosestrife’s new human servant, the brugh and its contents, which had once been so grandiose a work of fancy, began in many ways to change. Loosestrife found, to his great consternation, that his snuff box quickly ran out of snuff, even though he had expressly forbidden it to be empty. He found that the pillars of his house began to creak and groan, as if they could not abide the strain of their whimsical contortions. The fireplaces became cold and sooty, coming to realise just how unreasonable it was to be expected to provide warmth without sufficient fuel and kindling. Only the bluebells in the garden continued to defy Obtuse the servant’s inscrutable logic, pealing as usual each morning, and providing my dear friend with his only comfort. Even Loosestrife’s horse (a gregarious rabicano stallion named Claptrap) stopped speaking to him, for Obtuse had explicated in no uncertain terms that a horse’s anatomy did not allow for such a sophisticated expression of so wide a range of phonemes. All in all, and despite his wife’s protestations, Loosestrife was quite dissatisfied indeed with his new servant. He was of half a mind to cancel the grand ball he had arranged to show off his new status as a man who had gone up in the world, having invited several prominent faeries of excellent breeding and station: the aforementioned Tom Thistletop, of course, several lords and ladies, and even the Duke of Long Wind, who, though his conversation was known to be tedious in the extreme, was nonetheless (as it was often noted in the society papers) descended from King Auberon himself. In the end, of course, the desire to prove his social buoyancy in the presence of such fey and fair warmed any cold feet that may have troubled him.

When the guests arrived several days later, however, the house was almost unrecognisable by any respectable Faerie standard. The walls were straight, the beams of the roof were arranged all in a structurally sound criss-cross arrangement. The tables had legs, or else lay supine on the floor. The fireplaces were filled with coal, the clocks on the wall all ran at the same time, the mirrors reflected only what was put in front of them–even the cutlery no longer did as it was told, and had become complacent and lazy, needing to be operated entirely by hand. It was by far the most reasonable house that anyone in Faerie had ever seen.

Loosestrife had planned on converting the cosy little morning room at the front of the house into a majestic high-ceilinged ballroom, with lambent parquet flooring, marble columns, and several enormous chandeliers, but Obtuse had laboured the point that the dimensions and volumes of reality would not allow for such a thing, and the room had retained its original size, with little if any room for dancing. It was so poky in fact that the Countess de Winter’s voluminous gown of frost not only knocked over rather a lot of Loosestrife’s china ornaments (which in order to impress Obtuse insisted on smashing when they hit the floor) but also began to melt in the heat from the fireplace.

“Now listen here,” Loosestrife said after sneaking out to the serving pantry to scold his frustratingly scrupulous servant, “I want no more of your incessant reasonability tonight–you must be somewhat reasonable, of course, otherwise they will not believe you to be human, but please do your best not to be so pedantically logical. You have quite ruined my house, I have several very important guests in attendance, and I shall be very much displeased if you make this evening even a modicum less successful than it ought to be.”

At that moment, Marjory appeared at the door to the pantry.

“Marjory, my dear!” Loosestrife exclaimed. “Why, but a moment ago I saw you chatting to Martin Willowlimbs. What in all the realms could have possessed you to so hastily abandon one of our most important guests? Was his conversation not frivolous enough?”

Marjory smiled. “Quite, quite, he has a very fanciful way with words indeed, which kept me quite entertained. However, I had to tear myself away to consult with Obtuse here about the small matter of the canapés. You see–”

But Loosestrife simply waved his hand in dismissal. “I leave all that up to you, my dear. But do remember to hurry back. I have been told that my company is entertaining, but even I cannot be expected to singly keep a whole parlour of faeries enthralled for an entire evening.”

And with that he left to attend to the guests.

✸✸✸

Having returned to the far-less-than-adequate ballroom and taken up my customary position on the mantelpiece, I was pleased to overhear the following conversation between the Countess de Winter and the aforementioned Martin Willowlimbs.

The Countess: How strange this house is, my dear Martin. I have never seen the like. Why, everything is so orderly! I must confess it to be the dullest house I have ever seen. And they say Loosestrife has gone up in the world . . .

Willowlimbs: Indeed, Countess, his wife, too, speaks of the most dreary topics. She’s almost as bad as Long Wind.

The Countess: Is that the Greenteeth girl? Yes, what a strange slip of a thing. How unfortunate for her father to be so overcome with relatives like that.

Willowlimbs: How do you deal with them, my lady? I hear you have a large family yourself, and yet your wealth does not seem to have been leeched from you.

The Countess: Oh, swiftly, and sharply. They ask for much less money when they have no heads, you see.

Willowlimbs: Indeed, indeed, a wise course of action.

Loosestrife: Enjoying yourself, Squire Willowlimbs, Countess?

Willowlimbs: Quite, quite, my dear Loosestrife. But tell me, what is this strange way you have renovated your brugh? It is, uh-ha, somewhat dreary, is it not?

Loosestrife: Ah! You noticed. Well, my dear squire, Countess, you shall find out the cause of it soon enough. I have something of a surprise for you all, you see. Proof positive that I have indeed gone up in the world.

Tom Thistletop: A surprise, you say?

Jack Catkin, Marquess Arumhall: What’s this about a surprise I hear?

Loosestrife: Now, now, everyone, your lordship, my lady. All in good time.

Lady Arumhall: Oh, Loosestrife, don’t make us wait. Come now, show us your surprise.

Countess: Yes, do.

Willowlimbs: Go on, be a good fellow and show us!

Loosestrife expelled a long, considered sigh. “Oh, very well,” he said with apparent reluctance (although he could not, in truth, have hoped for a warmer reception to his surprise).

He marched to the head of the room, and stood on a stool in front of the fireplace. He picked up a miniature bell from the mantle, and when he shook it, it rang as loudly as the tenant of any belfry (it, too, must have escaped the attentions of the servant, Obtuse), dampening the chatter of those in attendance beneath the weight of its peals. The music stopped, the dancers came abruptly to a halt.

“My lords and ladies, dukes and duchesses, gentlemen and crones. As you are all aware, I have recently found myself going up in the world. From humble beginnings as a simple weaver of lightning thread, I worked diligently, investing my earnings in many sundry ventures, which have, as good fortune would have it, made me a man of not inconsiderable wealth. I built this most excellent brugh, acquired a friend who rides my coattails, and decorated my abode with the most frivolous furniture in all of Faeriedom. I have held parties and gatherings well-received and attended by the most prestigious guests”–here he paused to smile benignly upon them all–“but one thing I have been missing, one thing that will convince even the most staunchly feudal among you, that I, Loosestrife Foulweather, have a place among you.”

He rang a service bell. “I present to you, Obtuse, my new human servant.”

Gasps rose up from the crowd.

“A human servant! Why, there hasn’t been a new human servant in Faerie since Cottingley.”

“Offa’s Dyke! This is marvellous. A new servant in Faerie–why, I haven’t seen a human in decades!”

“Thistletop won’t be happy about this. He’s always been proud of being the last faerie to have had a working servant. Now an upstart from the shires has one! And not he! Such a scandal! Such a marvellous scandal!”

So were the mutterings of the Faerie gentry while they awaited the arrival of the human servant. But when minutes came and went and no human servant appeared, Loosestrife began to show the merest hairline fracture of concern.

“Tobias, would you tell my wife to fetch Obtuse, please,” he asked of me, sweat beginning to bead on the larger of his eyebrows.

“Your wife, Loosestrife?” I replied. “I know not where she is.”

“She is not here?”

“No, my friend, she is not.”

“Fornicating fauns! Then I’ll go and get them myself.” He grasped me by the shoulders and hauled me off the mantle. “You keep the guests entertained,” he said in a voice hoarse with panic, before rushing to the serving pantry to find his wife and servant. But no one was there. He rushed to his quarters, but no one was there. He rushed to every corner of the house, but his wife and his servant were nowhere to be found. Only, nailed to the front door he found a letter, written in two separate hands.

In a script clumsy and smelling slightly of cheese was written: To my former master, Every man having been born free and master of himself, no one else may under any pretext whatever subject them without his consent. I bid you farewell.

And below it, in the clear, sensible hand of his wife: To my former husband, I wish to be treated as a rational creature, I wish to feel the calm and refreshing satisfaction of loving, and being loved by, someone who can understand me. Adieu.

Loosestrife sat down upon a very reasonable seat in the very reasonable drawing room of his now thoroughly reasonable house. The guests slowly departed, and he said not a word to them as they left, though they certainly had plenty to say about him (of which I shall not repeat here for fear of setting your ears alight). He sat in the chair for many hours, while I, once more, took up my position on the mantle.

When the sun began to rise, he sat there still, and it wasn’t until the rays fully illuminated the world outside the house that Loosestrife realised he no longer looked out on Faerie, but rather on a strange and uniform landscape of closely tended gardens and dull square houses, lined up in neatly regimented rows as far as he could see. The sound of bells rang across the brightening morning from the tower of a nearby church, and strange dark forms wandered hunched along the streets, boarding oddly shaped carriages, which rumbled and roared in the morning air and left clouds of grey fog in their wakes.

A knock, suddenly, came upon the door.

“Marjory? Obtuse? Is it them, do you think, Tobias?” he asked me, rising from his chair and rushing from the drawing room before I could answer.

How peculiar I felt in that new morning light, as though my whole body had ossified–from exhaustion, I surmised, following all the recent excitement.

I heard him open the door. And a voice, not Marjory’s, nor that of Obtuse, came galloping down the hall.

“Mornin’, Mr. Fowler. How are you today?”

“Excuse me, miss, I . . .” Loosestrife began, but the voice had already entered the drawing room (now much smaller than I recalled it ever being before) and revealed itself as belonging to a young woman wearing what appeared to be a sky-blue housecoat. Loosestrife followed her, and I must admit that now, in the fullness of the morning light, I could see how the strain of last night had changed him. His face was wrinkled and veined much like the cheese we had used to coat Obtuse’s wooden frame, and his posture was as crooked and contorted as the walls of his house had once been.

“Now, then,” said the woman. “I’ll give you your medicine first, and then I’ll make you a nice cup of tea. Then we’ll get you washed and dressed; how does that sound?”

“What is she talking about, Tobias?” he asked me, his eyebrows quite nearly leaping from his head.

The bluebells outside rang in the wind–but wait, it was not the bluebells; the ringing came from the intruder. She dug about in her pocket and lifted what looked like a pink snuff box to her ear.

“Hi, babe,” she said, apparently addressing an infant that had somehow entered the room unannounced. “Yeah, I’m at Mr. Fowler’s house now. Yeah, I’ll be done in about half an hour, all right? I’ll drop it round for you after I’m finished.”

“Tobias! What on earth is going on here! Who is this woman?”

“What’s that, babe? No, that’s just him talking to that flippin’ Toby jug on top of the fire. Yeah, yeah, all right, babe. T’ra.”

(I have done my utmost to transcribe her eccentric way of speaking, but I make no claims on its accuracy. It was indeed a most babbling and incoherent dialect.) She continued:

“Right, then, Mr. Fowler. Let’s get you that cup of tea, shall we?” She smiled a sweet smile, and left the parlour. I heard her going down the hallway to the kitchen.

“Tobias,” Loosestrife said to me, quickly approaching the mantelpiece. “I think this may be our replacement servant. Oh, yes. Oh, yes! Now everyone will see how I’ve gone up in the world. Another party, do you think, dear friend?”

To this I said nothing. Having experienced quite enough excitement of late, I thought it best not to encourage my friend any further in his fancies. I merely stared, and chewed on my pipe in silence.

This story previously appeared in Deep Magic, August 2017.

Edited by Marie Ginga

Dafydd McKimm is a speculative short fiction writer whose work has appeared in publications such as Deep Magic, Daily Science Fiction, Kaleidotrope, Syntax & Salt, 600 Second Saga, Flash Fiction Online, The Best of British Science Fiction, The Best of British Fantasy, & elsewhere. He was born and grew up in Wales but now lives in Taipei, Taiwan. You can find him online at www.dafyddmckimm.com.