Because our days were so exhausting, I was usually out the instant I hit the pillow, entering a deep and perfect sleep the dreams of which I could not recall; on other days, the work continued—the only difference being that in the dreams I flew over the island like a hawk (rather than search it house by house, or, just as often, beach café by tiki bar); and was able to spot a bread crumb even while soaring high enough to see most of Alice Town (though not so far as Bailey Town). And always, always, I returned to the Bimini Big Game Resort and Marina, with its ruined, capsized boats and broken, shattered docks (now undulating against the seawall); its multiple floors and long, red roof—which, only weeks before, had been the only thing standing between Búi and I (and Amanda, too) and the tsunami. Nor did I merely revisit it in my dreams, for it was where I started and ended each day’s search regardless of how much of the island we’d cleared (we’d reached Resorts World Bimini—the approximate halfway point between Alice Town and Bailey Town). It was where I was at, looking at Búi’s many half-filled water glasses, when I heard Amanda’s voice crackle suddenly, startlingly, over the walkie: “Sebastian, I’m a few houses past Resorts World—on the state-side of the key. And, ah, you’re going to want to see this.” She quickly added: “It’s not a body, nothing like that. It’s nothing to do with Búi. Just—get over here.”

I stared out across what was left of the marina; at the crystal clear water and the reddening sky—in which a solitary pterodactyl whirled—and the golden clouds, like heaps of fleece pillows. Her tone of voice had given me pause. “Sure. I—I was re-checking the Big Game. The Bar and Grill. I’ll … I’ll head up right now.”

And I went, hurrying to where the Jeep was parked in front of the Sue and Joy General Store and laying the flare gun on its passenger seat—before turning the ignition and heading up Bimini Bay Way, staring between houses as I drove and peering into their tall windows (although for what I wasn’t sure; we’d already checked them for Búi and their original owners had long since vanished in the Flashback). It was easy to do; driving so carelessly—there weren’t any other drivers or pedestrians to think about; only the Compies scattering before you like flightless gulls or the occasional newspaper or plastic bag. That’s how it had been since the Event; and, as a consequence, you tended to get to where you were going quickly and effortlessly, before the melancholy of the place could really sink in (it was the seeing of it all at once that did it; the sheer totality of all that emptiness blurring past), something I was immensely grateful for as I turned left on Queen’s Street and jounced onto the beach—and saw Amanda’s Prius parked next to the overturned truck and custom boat trailer; next to which lay, well, whatever it was. Because it looked like a kind of miniature submarine, only shaped and painted like a shark, replete with rows of sharp teeth. It even had a dorsal fin.

“What the hell is it?” I asked, getting out, then hurried to help her as she shouldered her rifle and gripped the thing by a fin.

“Seriously?” she asked. The sand loosened and slid from its hull as we pulled the object upright. “It’s a Seabreacher.” She stood back and dusted her hands. “Sort of a jet ski, only enclosed. It—people use it to dive under the water … then breach the surface, like a dolphin.”

I stood and looked at it—at the Seabreacher. “Okay. Great. And this helps us—”

“Don’t be obtuse.” She moved forward and tried the hatch handle, which turned—then opened the cockpit, slowly. “Seats two. Might even be able to slip in a third. Knew a guy before the Flashback, said he could pilot his all the way to Miami. That’s what I meant by, ‘Don’t be obtuse.’ It means we’re not stuck here.”

I must have looked—unenthused.

“That’s a good thing,” she said. “In case you were wondering.”

“A good thing,” I said, and looked back the way I’d come.

“Yes, a good thing.”

I focused on the small church further back along the beach—Gateway Outreach Ministry—which we’d already checked. Except for the sacristy, which had been locked (this had been before we found the rifle). Wasn’t it at least possible she’d taken refuge inside it?

“Sebastian …”

The answer, of course, was no. She’d have responded when we called out (and we’d called out a lot). But what if she were sick, or wounded— unconscious, even? What if she’d been unable to hear us, or to respond even if she did? What if she’d been too debilitated to reach the door? Was it really magical thinking to suppose—

Amanda exhaled, defeated. “Sebastian … what can I do?”

I turned to look at her as she shrunk down in the sand, looking more tired than any twentysomething had a right to—more haggard, her eyes vacant and puffy, her cheeks sallow. “I mean, how long do you think they’ll last? One small, overgrown grocery store … and a mini food-mart? (by ‘overgrown’ she’d meant the ubiquitous moss and vine—presumably prehistoric—which had come, along with the Compies and the pterodactyls, immediately after the Flashback) Six months? Couple of years—if we’re lucky?”

I scanned the nearby homes. “Longer than that. Plus there’s the bars and restaurants—not to mention all the houses.” I looked at the darkening horizon. “It’ll be light for a while. We should keep searching.”

I felt her eyes follow me as I walked toward the Jeep.

“Sometimes I don’t know what you want from me,” she said.

I paused before climbing in. “I want you to help me find my wife,” I said.

After which, realizing how cruel that had been, how unfair (for she’d been helping me tirelessly), I added, “You should get some rest. It’s—it’s going to be dark. I’ll push on from here; okay? Don’t wait up.”

And I put the Jeep in gear.

✸✸✸

The first thing I noticed when I got home to the duplex—it must have been around midnight—was that Amanda’s unit was dark while mine was illuminated; something quickly explained when I swung open the door and saw the burning candles, not to mention the tinfoil-covered plate and half bottle of wine; or, for that matter, the greeting card-sized envelope—from which I withdrew a letter that read, simply, Happy 50th, S.B. We’ll find her.

I guess I must have smiled.

“S.B.” —Sebastian Adams. She had a memory like a steel trap.

I lifted the tinfoil and peeked at the dish—a fusilli pasta topped with white marinara sauce—but wasn’t any hungrier than the last time she’d cooked; and merely re-covered it. I looked around the table. That wine, though.

I snatched it up and fetched a glass (funny she hadn’t left me one) and then went out onto the deck—startling a Compy in the process, which leapt from the round table next to my chair and strutted—its little head bobbing, its tail jouncing—across the planks; into the cycad bushes.

“Boo,” I said.

Then I settled in: propping my feet on the stool and looking out at the Atlantic, purposefully ignoring the little framed picture of Búi; disregarding the spilled peanuts and disturbed water glasses, some of which had been knocked over and some of which remained standing, but all of which contained or had contained small amounts of water, because now I was doing it (wasn’t it funny, how couples could rub off on each other?).

“Tomorrow we’ll do Resorts World,” I said, still not looking at the picture. “If that’s okay with you. I mean, it’s like I’ve always said: You’re the boss. No, no, that’s how I want it. You should know that by now.”

I took a drink straight from the bottle, which Amanda had left open, and exhaled. Then I tipped it again and drained the entire contents. “Well, honey, you wanted purple yams, remember? But it looks like your dinky dau sense of direction finally got the best of you. So you lost your way and mistook north for south; and now you’re probably on the other side of Bailey Town—alone, confused, and terrified, I’m sure.”

I looked at the sky—just a vast, black pit, mostly, like the ocean—but didn’t see any lights, nor the prism-like jewels that had hung there since the Flashback—the time-storm; whatever—I suppose because of the clouds.

“Or … have you disappeared to somewhere else; like everyone else on this island? Another time, another place, another epoch …” I lolled my head against the backrest, woozily. “What the hell is this Flashback, anyway? I’ll tell you what I think; I’m afraid Time itself has somehow been changed so that half the planet never existed. I’m afraid the first wave took the others and the second wave brought the dinosaurs and a third wave, well, a third wave took you. Because, honey, I’ve searched … and searched … and you just don’t seem to be here. Not fucking anywhere.”

A moment came and went; a moment in which I might have shattered, a moment in which I was capable of anything. But, as I said: It came … and it went.

And then I did look at her picture; at her round, youthful face (although we were both precisely the same age), and her large, straight teeth. At the big brown eyes I’d often joked would eventually outgrow their sockets (to just dangle from their stalks, I’d said), and her ability to smile for the camera even after a terrifying ride in Miami (with a drunken boat captain) had almost ended our vacation—and our lives. At the girl from Bình Du’o’ng Province, South Vietnam, whom I’d married 7 years prior and experienced the initial Flashback with—as well as the meteor-caused tsunami which had happened immediately after—but who had then vanished without a trace on a trip to get purple yams. And chia seeds.

I laughed a little at that in the warm, bitter darkness, wondering if she’d ever found them.

“I bet you did,” I said, my faculties beginning to fade, the wine beginning to kick my ass, before reaching out and laying the picture face-down on the table.

And then I slept, and eventually dreamed; of the island as seen from the heavens and of floating through a kind of limbo, a kind of purgatory. Of passing over Alice Town and Bailey Town and on to the open sea, which was infinite. Of being joined by another so close that our wings brushed, and flying—not like Icarus, not like Daedalus—but purposefully, fearlessly, without regret, into the ancient, seething, fire-pit cauldron of the sun.

✸✸✸

Of what went through my mind when I saw the turkey-sized predators congregating at the end of the jetty (or rather the start, for we were heading back toward shore from the ferry terminal), I have no memory; other than to say I’d felt suddenly good, suddenly content, while striding along beside Amanda over the lapping surf (and laughing at some joke), and that, when I saw the predators, all of that just went away, just drained from the world, like the sun going behind a cloud.

Because it had been a good day; the first since Búi had disappeared. Nor could I put my finger on why, exactly: maybe it was simply because the weather had been so agreeable; or because the company had been so good. Maybe it was because we’d cleared an entire block of houses as well as the ferry by late afternoon and I’d been reminded of just how many places—safe places—she could still be. Or maybe it was because I’d forgotten, however briefly, that the world was a necropolis: a windswept graveyard, and that we—Amanda and I—were likely the last living souls.

Until we were coming back along the jetty from the ferry, that is. Until the slim, lithe predators with their long, dark tails and blue-gray coastal-patterns; their white, unblinking eyes, their little, undulating mohawks comprised of blood-red feathers, saw us.

“Are those—what did you call them? Comp—compsognathuses?” asked Amanda. “They don’t look the same, for some reason.”

I peered at the animals—just animals—through the shimmering heat: the three of them having become four, the four of them about to become five (as yet another emerged from behind an abandoned SUV) … no, six.

“No,” I said, absently. “I don’t think so. They’re too big.”

I watched as the things seemed to focus on us, one of them shaking off while another used a foreclaw to scratch itself behind the ear. “Plus, they’ve got longer arms. And those toe claws; they’re extendable—you can see it from here. More like a deinonychus (I had a dinosaur encyclopedia back at the duplex), or a—”

“Or a what?” She stared at the animals as though she were seeing a ghost. “Or a velociraptor, like in Jurassic Park?” She started to back up. “Because if that’s what you were going to say, don’t. Besides, they’re too small.”

“Movies exaggerate,” I said—also backing up. “Just easy does it. They’re as scared of us as we are of them.”

But now there were more, about twelve at least (with still more streaming in), one of which darted forward abruptly … and then hesitated, craning its neck to look at the others and shrieking—angrily, it seemed—just like a bird.

“Yeah,” said Amanda. “That’s bullshit. Look at them. There’s strength in numbers.”

Alas, I was looking at them, at their eerily intense focus (like cats starring at a pair of robins) and their coiled shanks; at their tails which were moving back and forth like knives.

I felt my vest for the other flares and touched the heel of my knife. “They’re going to try and rush us; we’re going to have to run for it. Are you up to it? I’m thinking all the way to the ferry … how about it?”

“It’ll bring them on, I guarantee it …” She unslung her rifle and looked over her shoulder. “I don’t think we can make it. I mean—wait … what about that island shuttle?”

I watched as the others filed after the first and they regrouped—just a gaggle of heads and tails—then glanced at it myself. “Forget it. It’s got a canvas roof— remember?”

“With steel ribs, though.”

“Yeah, but—we’d be stuck. There’s no key.”

And then they were coming, not in a gaggle but in a staggered formation, bounding forward but in turns, running and pausing, as we turned and flat-out bolted—sprinting for the ferry as the sun shone hot and merciless and without compassion; veering for the island shuttle once we realized we’d never make it, piling through its driver’s door and slamming it behind us as the raptors fell upon the vehicle like a threshing machine and began climbing and tearing at its canopy.

“Wait, don’t—”

My ears rung as she started firing, blindly, into the animals, at least two of the slugs hitting the beams and ricocheting—one of them close enough to nick my ear.

“There’s too many of them,” I shouted, even as a dark snout stabbed between the beams and banged to a halt, gnashing its teeth. “Just stay low, they can’t get through.”

After which I eased the rifle from her hands and we hunkered near the floor; the raptors screaming and tearing the roof apart even as ragged pieces of it fell and they began reaching between its beams with their human-like forelimbs—swiping at us with their curved talons, blindly; reaching and groping and searching—like zombies.

Neither of us behaved bravely or kept our wits about ourselves. It was the screams that were the worst; which tore through the air like knives—like fighter jets passing so close you could see the rivets. Which split your mind so that you were too disoriented to think, to do much of anything. I’m afraid they got the better of us both as we cowered near the floor and covered our ears; as Amanda reached for me and pulled me close and I wrapped her up in my arms and squeezed her tight.

“Just hold me,” she said, as the entire vehicle rocked and shook around us. “And don’t let go.”

And so I held her and didn’t let go; cradling her head in my hands as the raptors screamed and continued their assault—as the entire truck was lifted on one side only to crash back down, as she said almost softly, “We—we have a responsibility. I never told you. A purpose. Because … we’re the last, and someone … someone has to continue. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

I squeezed her tighter even as the glass and canvas rained down. “Shhh, save your strength. They’ll give up and go away … we just have to wait. Just—hang in there.”

More broken glass; more shredded canvas. I squeezed my eyes shut; I was no longer certain they wouldn’t get in.

“I want you to promise me, Sebastian. Promise me you’ll meet me there—no matter what. Because if not us, then who?”

The raptors cried out in unison—like a perverse choir; it was almost as though they were celebrating, like this was their victory song.

I pulled back enough to look at her; at her dark blue eyes, so much like my own, and her youthful face—which was beautiful by any measure—understanding with perfect clarity what she’d meant; and realizing, too, to my great and utter astonishment, that I agreed; that we owed the world that, every bit as much as I owed Búi. That it was our duty, in a sense … to ensure the bloodline survived; to propagate the species. And I realized something else, now that we were so close we could smell each other’s sweat and I could feel the back of her hair against my hand and her body pressed against my own—like a rock; now that I had a raging hard-on in the face of what seemed certain death, God help me. And that was that I wanted to live. Irregardless of if we found Búi or not; I wanted to live—to continue the journey—to spit in the eye of whatever had selected me for extinction, whatever had selected Búi for extinction, selected the whole world. Whatever had just crossed us out like a grammatical error: ‘Remove this,’ and scrubbed us from the sands of Time.

That’s when we noticed it; at precisely the same instant, I’m sure. That the sound and the chaos had stopped. That the raptors, the screamers, the bloody things, had called off their attack. That the world had gone quiet again and we could hear the water lapping against the jetty’s pilings.

We disengaged from each other and got up—looked out the driver’s side window.

The majority of the horde was gone. We were still trapped; there remained about six animals—yes, six, exactly—but the larger pack, the larger pod, herd, murder, whatever, was gone.

I picked up the flare gun (which I’d found in the wreckage of a yacht after the tsunami, when Búi was still here), and unsheathed my knife. Amanda did the same, chambering a round in the Marlin rifle and taking out her own knife.

We never discussed it; never weighed the pros and cons of what we were about to do, never questioned what we were both feeling, which was that we wanted to live, and to not be afraid. We never asked the other if it was the right thing or the wrong thing—if it was worth the risk, say, when the other raptors could come screaming back at any moment. We already knew it was the right thing, because it was the only thing. Instead I just gripped the door handle and looked at her, and when she was ready—she nodded.

And then I threw open the door and we piled out.

There were six of them, as I said—all of whom rushed us the instant our feet touched the ground. All of whom snarled and charged us like wolverines as we raised our weapons and fired—the flare gun cracking and hissing, blanching the scarlet haze (for the sun had painted everything red and gold), its projectile punching through one of the raptors’ chests and lighting it up so that its ribs were backlit briefly and I could see, if only for an instant, its burning, beating heart.

Yet still they came, another one leaping at me even as I dropped the gun—which clattered against the planks—as I dropped it and grabbed the thing by its neck—then brought the knife down with my other hand and stabbed it between the eyes.

“Run!” I shouted, even as Amanda shot another—her second—and then bolted toward the shore, drawing the others so that I was able to snatch up the flare gun and quickly reload it; so that I was able to pursue them and to shoot one in the back—while Amanda turned and took out the last of them (shooting it in the head so that the back of its skull exploded like a spaghetti dinner thrown against the wall; so that it collapsed, writhing, about 10 feet in front of her—whereupon she quickly approached it and shot it again, just to be sure).

And then she looked at me (as the dead and dying animals lay all around us) and I looked back: our chests heaving; our faces covered in sweat, our worn clothes bloody and disheveled, and I knew that she knew—which was that today we were the predators, the thing needing to be feared—the killers. And that neither of us needed to worry; not about food or other predators or mysterious lights in the sky or anything. Because we were the masters of our fate, we and no one else, not even God. And we were the master of the world’s fate, too.

At which she ran to me and we collided and I held her fast, there on the long jetty in the Atlantic Ocean (in the Bermuda Triangle), there beneath a day moon and the blood-red sky, in an instant in which it was good, so very good, not to be afraid, not to be alone. And as to what may or may not have happened in those breaths, those pulse points between that moment and the next—the next day, the next search, the next milestone; as to that, I offer only a quote from Gandhi: “Speak only if it improves upon the silence.”

✸✸✸

It’s possible I’d never felt so alive as when we took the Seabreacher out the next day. All I know for certain is that diving into the gurgling darkness at 50 miles per hour (and then breaching again, like a dolphin) turned out to be a lot of fun; so much so that we spent the better part of the morning doing just that: diving and breaching, plunging and rising, racing up and down the island (and around its horn, to Pigeon Cay) like damn fools; like college kids on a spring break, which I suppose Amanda was.

That is, until we broke surface and saw the meteor, which was arching across the sky like some orange and black torpedo—like some great, cyclopean flare—painting a trail of smoke and fire as though driven by God Himself; shedding chunks and pieces of itself, like an avalanche. Nor did we slow and try to see where it impacted but rather steered for the shore straight away, beaching the Seabreacher in the shallows near the Big Game Resort and Marina and popping its jet-fighter-like hatch, clambering out of it swiftly as the meteor vanished beneath the eastern horizon and the sky exploded: first yellow, or rather a kind of golden amber, then orange, then pink, and finally, after several moments, blue again—although not before the shockwave hit us and blasted us off our feet—straight onto our backs.

“That … that hit about the same distance away as the first one,” I said—after we’d caught our breath and determined neither of us were seriously hurt. “Holy shit.” I stood and dusted myself off, then peered at the glowing horizon. “Different location, but same basic distance.” I must have looked white as a ghost. “Jesus—another P wave. Another primary. And that means—”

“Another actual wave,” said Amanda. “Another tsunami—headed this way.”

She glared at me and I glared back, both of us knowing full well what that meant. We had about two hours. Two hours before it hit and all hell broke loose. At the max.

She looked at the Seabreacher, which gleamed in the sun, then into its cockpit. “We’re going to need that fuel can; the one from the truck. And supplies: food, water, a way to start a fire—”

“Now wait just … I can’t—”

“Do you want to live or not?” she snapped— before placing her hands near the Seabreacher’s caudal fin and pushing, trying to turn the boat around. “Because I do. And there’s only a quarter tank left in this beast—which isn’t enough.”

I knelt beside her and helped; shoving as hard as I could, sinking and sliding in the sand—until we’d succeeded in turning the thing around.

“Okay,” I said, leaning on the metal, our faces close. “I’ll go to the duplex and get the gas—if you want to hit Sue and Joy’s and see what you can find. Definitely some bottled water. And a lighter—several of them, if you can. Some toilet paper wouldn’t hurt. We’ll meet back here in, say—twenty minutes. No later. Okay?”

She looked at me uncertainly, compassionately. “You want to get your picture—don’t you? I saw it next your chair. When I—when I left your birthday dinner.”

I stared at her for a moment before lowering my gaze, focusing on the sand. “To prove she existed,” I said, almost whispering. “To show that—that she was here. She deserves that.” I looked out over the ocean. “So do I.”

“Well—go get it, then, Sebastian. Go get it and get the gas can and get your ass back here. Because I can’t do this alone.”

And we went—on foot (our vehicles were still parked where we’d found the Seabreacher; on the opposite side of the island): Amanda splitting off for the General Store while I continued on to our duplex, which wasn’t far. The hardened twentysomething going one way while I went another—haunted, guilt-ridden, alone.

✸✸✸

Understand this: while it certainly was a T. rex—or something very much like it—it was not, by any stretch, a monster. It was not, for example, Godzilla (or any other behemoth as depicted in popular movies and books; including, I dare say, Jurassic Park). No, this was just an animal, big as an elephant, it’s true (but no bigger), and yet, ultimately, no more outlandish than a spotted leopard or a crocodile (at least not since the Flashback); meaning it played well enough with its environment that I hadn’t even noticed it—until it was too late.

Too late to get a shot in, anyway—not too late to run; which I did, dropping the gas can and bolting (even as the rex paused to sniff some spoor) before coming to a massive tree (a Caribbean pine, as I recall) and—after jamming the flare gun into my waistband—starting to scale it.

Alas, I’d barely attained the middle limbs when the T. rex arrived—its jaws snapping shut only inches from my shoes and its bellows echoing, furiously. Yet there was little it could do; I’d already climbed beyond its reach (and was climbing higher still). And so we tried to wait each other out, the tyrannosaur and I, as fragments of the meteor began lancing the earth and the doomsday tsunami drew inexorably closer. As the clock ticked mercilessly and Amanda surely fretted and Búi seemed almost to whisper in my ear: Where have you gone to, my husband, my love, and why have you abandoned me? Is it not obvious—so very, very obvious-—-where I am? Why, oh why, can’t you see?

At which, inexplicably, I did see—something.

A roof.

Just a roof.

Indeed, there wasn’t even anything special about it—this roof, other than it was attached to a house I had not seen from the ground—and so had not searched.

I rubbed my eyes and looked at it a second time.

How could we have missed that? Right here, in a wooded section of Alice Town? Right here—not even a block from the Big Game Club Resort and Marina?

I gazed out over the treetops, toward the ocean—and saw it. Saw the wave. Or at least a band of white along the horizon that looked like a wave. Was it possible? Búi—I mean? Had she gotten lost—or even injured—and just wandered into the first house she’d come to?

And did I have the time to find out?

And then something just snapped and I was taking out the flare gun and aiming it into the rex’s mouth and squeezing the trigger—even as Amanda appeared at the corner of my vision and trained her rifle—after which the rex’s maw lit up like a firework and blood jetted from its head (for that’s where Amanda had shot it) and the tyrant lizard just collapsed—not threshing about like in the movies, not unfurling its foam latex or CGI tail, but simply slumping forward into the grass like a beached whale until the tip of its snout touched the tree and it was gone. After which I quickly climbed down.

“See?” she said, and chambered a new round. “We make a helluva team.” She frowned a little as though she’d just thought of something. “Where’s the gas?”

I nodded to where I’d dropped it—about 50 feet away.

“Thank God,” she said. She slung the rifle over her shoulder and moved toward it—then paused. “What’s wrong?”

I think I just stared at the ground. “I—I spotted something … up there in the tree. Something we missed. It … it’s in that woodland—right next to the duplex.” I lifted my eyes to look at her. “An entire house.”

She only gazed at me, saying nothing.

“So, what,” she said, finally, “You’re just going to mosey back up there and check it out—with the wave practically on top of us? Is that it?”

I nodded, slowly. “Yeah. That’s about it.” I reached out to touch her but she slapped my hand away. “I’m sorry,” I said.

She glared at me as though she might strike me. “Oh, you will be, Sebastian. You will be. Just as soon as that wave arrives.” She started to storm off but stopped on a dime. “And for what? Another empty house? Another room full of ghosts? Because there is nothing here, Sebastian. We’re it.” Again she started to go, and again she stopped. “What—you think you’re the only one who’s lost someone? The only one who’s lost a wife, or a child, or their parents? Well, I’ve lost people too—everyone I’ve ever known. I did! Amanda Everett.” Her eyes welled up suddenly and profusely and she swiped at them. “Just because I’m younger than you doesn’t make it any easier. And yet we’ve been given this chance, Sebastian. This one chance to face it together; to reboot the world. To literally save it. To make babies, for God’s sake. And you just want to—you want to—”

And she came at me and we collided, briefly, before embracing—not forcibly (even violently), as had been the case on the jetty, but gently, softly. And then I handed her the flare gun.

“Take it—please,” I said. “It—it needs to be with you. And the boat.”

She hesitated, staring at the thing, before offering me the rifle, which I declined. Then she took it—the flare gun—decisively, resolutely, and stuffed it beneath her waistband.

“I’m going to wait for you as long as I possibly can, okay? Understand? Five minutes before I leave—I’m gonna to shoot a flare; that’ll be your signal to drop anything you’re doing and to run, not walk, back to this location.” She stared at me with conviction. “Okay?”

“Look, you don’t have to—”

“Ah, but I do,” she said, and held out her palm. “No less than you have to go check out that house. The flares, please.”

I dug them out of my jacket and handed them to her—there were only three. “You shouldn’t wait too long. I mean, who knows how big this one will be, or how fast it’s moving. But okay. One flare equals five minutes.” I stepped back to look at her—to take all of her in. “It—it wasn’t just because—”

“Shuttup. Just … just go do what you got to do. All right?”

She moved to leave but paused.

“Five minutes,” she repeated, and then really did go.

✸✸✸

What was I feeling as I ascended the stairs to the upper (and last) bedroom of the house? It’s impossible to describe; other than to say ‘despair’ is too weak an expression. No, this was hopelessness and anguish as I could not have imagined—not in my loneliest dreams and nightmares—made worse, no doubt, by my fantasizing along the way; by my sheer, undiluted optimism that each step had somehow brought me closer to my Omega Point, closer to Búi.

But the steps had not been kind—nor had they been quick. And by the time I opened that final door to the final room I had largely succumbed to the inevitable; by which I mean I hardly gave the space a glance—seeing only a jumble of blankets on a four-poster bed and a rickety nightstand crowded with half-emptied bottles of water—before quickly turning to leave.

At which, before I’d even gained the stairs, I froze. Dead in my tracks.

The bottles of water. The plastic containers labelled Aquafina and Dasani—all of them half-full.

My heart thumped against my chest.

“Honey?” I said, in the near perfect silence, “Are you there?”

And then I waited; feeling that even an apparition; even a ghost, a chimera, would be welcome. But there was nothing. Not so much as a creak in the floor. Not so much as a rustling curtain.

But then there was something. Just the smallest of voices—indeed, a sound so faint I might have imagined it. Just a small, feint voice which said, simply: “Honey? Is that you?”

And—Dear God—I scrambled; rushing back into the room without a moment’s hesitation; finding her head exposed outside the tangle of pillows and blankets.

“Honey! Honey!” I knelt beside her at the head of the bed—between her and the open, curtainless window—placing my hands upon her: one on her stomach and one on her head. “Are you all right? Jesus, how have you …” I looked around the room and saw several empty cans—Dinty Moore Stew and Jack Mackerel, mostly, one of which was entertaining a rat. “Can you move? Can you move, honey? ‘Cuz we gotta get you out of here. And I mean, like, now.”

I suppose that’s when I noticed it; that her eyes were jaundiced and her skin had turned a sickly yellow. And I knew, also, even before I asked her (and she explained it), precisely what had happened: for she had been bitten by something poisonous—a breed of Compy, she said—and had stumbled her way into the house, where she’d been lying, delirious and partially paralyzed, for some three and a half weeks now. Nor was she going anywhere, because the paralysis had presented itself as a kind of full-body muscle spasm, which meant even the slightest movement could cause her excruciating pain.

“But where—where are we now?” she managed—and was interrupted by a coughing jag. “I mean, I remember getting lost; and I remember being bitten, and I remember being stuck in a house for a long, long time. But what I don’t remember is how I got here … with you.”

I moved to respond but paused, listening. For there was a sound now. A kind of low rumble—which rattled the panes.

I clasped her hand in mine and stroked her forehead, tidied the strands of hair. “We’re home, honey. We’re back home now. In our stupid little apartment. And—well, it’s been a wonderful day, just really nice. We went to Greenbluff—do you remember? To pick cherries. And you picked so many you could hardly carry your buckets, so I had to do it for you—as well as carry my own; but that was all right because I started singing “Beast of Burden” by the Rolling Stones—you know, how I do: badly—and it made you laugh; which to me has always been the best sound in the world. And then we went and got pizza and ate it in the car, and after that, went to my Dad’s—to celebrate his 89th birthday. And it was wonderful, just wonderful, with all of us there and the dogs chewing on our shoes and the sky sheltering everything like a big, blue dome; and later, like a dark umbrella.”

I heard a crack! and a whoosh and a fizzle and looked out the window; saw the flare rising high like a rocket bound for the Moon: just rising and rising and leveling off—even hovering, briefly, like a UFO—before beginning its glorious fall, its sparkling and brilliant demise, its deep and fatal dive into the Big, Vast Nothing.

She rolled her head on the large, dirty pillow. “Is it—is it the Fourth of July? Are we watching fireworks?”

“Yes, sweetheart, we are.” I moved out of her line of sight. “Look at it, sweetie. See how it sparks and shines.”

“It’s so beautiful,” she said. “But what—what on earth is that other thing? That sound? It’s like—it’s like thunder, almost. Or an earthquake.”

I moved around to the other side of the bed and got in—nuzzling up against her, holding her so we were perfect spoons. “It’s the fireworks, honey, echoing off the buildings. It’s nothing to be afraid of. Just a sound. Remember—remember when we went to the Air Show that year, and the sound of the jets scared you so bad that you started hyperventilating? And do you remember what I said to you, that you should just count to 10—and breathe?”

She nodded, her black hair tickling my nose, as the rumbling became a thunder, and then a roar.

“Try that now, okay, sweetie? Just count to ten and breathe, all right? Go ahead.”

And she started counting, her voice clear and child-like, her accent as strong as ever. “One (inhalation) … two (inhalation) … three … four …”

“Remember to breathe, honey; do it after every number. I’m right here. We’re all here. Your children and your parents and my Dad and all your friends. We’re in this together—every one of us. And I love you. More than you will ever know. Goodnight, honey.”

“Eight … nine … ten.” There was a moment of silence, or so it seemed. “I love you too, sweetheart.”

And then came the waters, surging, crashing, churning, roaring.

And we just breathed.

Deeply.

✸✸✸

And yet we did not die—not really. Rather, it felt as though I slept, dreaming … of the island as seen from the heavens and of floating through a kind of limbo, a kind of purgatory. Of passing over Alice Town and Bailey Town and finally out to sea: where a grain of rice turned out to be the Seabreacher. Of watching that Seabreacher skip and jounce over (and through) the waves like a dolphin—heading toward Miami—and knowing, somehow (for I could see the future now as though it were laid out before me, like a tapestry), that it contained not just Amanda but the dreams and aspirations of all mankind; and that I’d had a part in that.

And, lastly, of being joined by another—so close that our wings brushed—and flying, not like Icarus, not like Daedalus, but purposefully, fearlessly, without regret, into the ancient, seething, fire-pit cauldron of the sun.

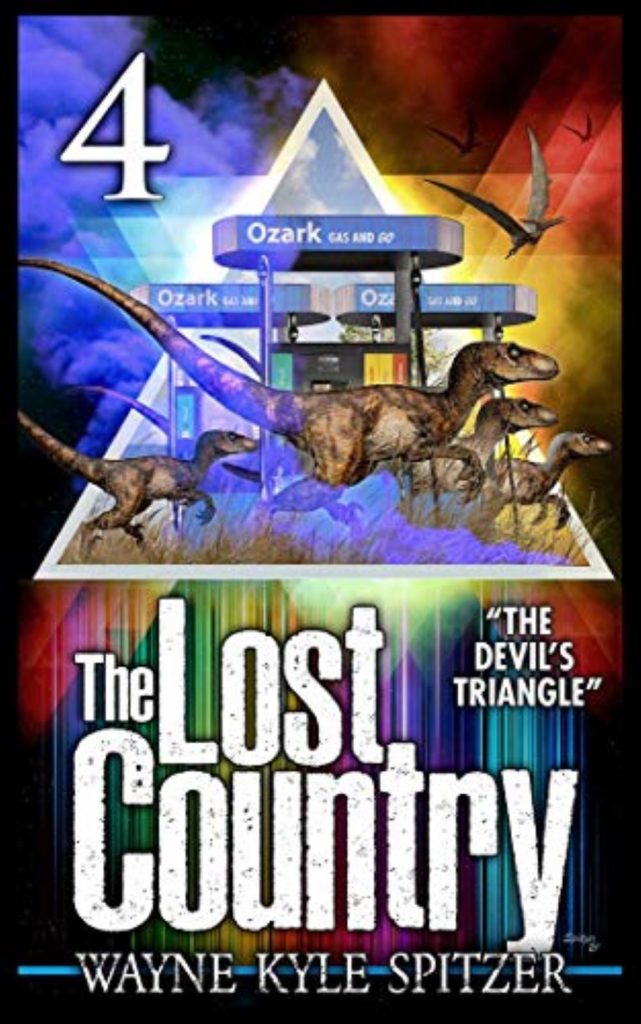

The Devil’s Triangle was first published in March 2021 and is the fourth story in a series entitled The Lost Country.

Edited by Marie Ginga.

Wayne Kyle Spitzer is an American writer, illustrator, and filmmaker. He is the author of countless books, stories and other works, including the film Shadows in the Garden, the screenplay Algernon Blackwood’s The Willows, and the memoir X-Ray Rider. His recent fiction includes The Man/Woman War cycle of stories as well as the Dinosaur Apocalypse Saga, all available on Amazon. He lives with his sweetheart Ngoc Trinh Ho in the Spokane Valley.