Deep in the dry woods

where the seer-witch dwells

stirring up her nasty spells.

Beware, you young ‘uns!

Brush your teeth and get yourselves to bed,

or the madame-witch will boil your brains

right inside your head!

Deep in the dry woods

where Madame Sosostris dwells.

– Lynchworth children’s rhyme

Cal carefully placed the second box beneath the crooked windowsill. Both wooden boxes, one for each foot, were furry with moss and smelled of putrid fruit. He wondered if the witch (whose house they were about to peer into) used them to collect fruit from the groves beyond the ravine – contrary to Daisy’s belief that the old hag didn’t eat normal-people food, only pulverized baby flesh fried in cat urine.

Cal looked back at Daisy. It was difficult to make out her expression in the half-light, cast by the hesitant moon, but he was certain that his friend was scowling at him.

“What?” she whispered.

“Are you going to have a look?” Cal said.

“You said you were going to.”

“I don’t recall saying that.”

“You are such a liar–”

“Shh!”

A low hum was coming from the house; it seemed to be pushing up against the dirty windows. Daisy thought it sounded like breathing.

Cal whimpered, “Should we go? We should go.”

Daisy rolled her eyes in the dark. She stepped up onto the boxes and reached for the window ledge.

“What do you see?” Cal said.

“Nothing yet!”

Daisy straightened her legs to get a better view inside the cramped house, aware of the frail boxes bending beneath her feet. The glass was fogged with grime, but she could make out the spiky light of a fire in the corner. Ornaments and crooked things woven with straw, mysterious tools and pans and black pots glazed with cobwebs, hung from the ceiling. Something out of place was hanging among them – a thin line of twinkling light cutting through the murk, which Daisy realized was a chain, tethering a bird in the attempt of flight.

“Oh my! It’s the necklace! I knew it!”

“You did not.”

“Did so.”

“Did not–”

“Shut up. Wait–”

Daisy moved her face closer to the window until her nose was squashed against the glass. The fire flared with a loud hiss and she saw something else in the flickering shadows; a serrated ring of stacked stones, slicked with moss, in the middle of the room.

“There’s something else. How strange!”

“What is it?”

“Well … it looks like a well, I suppose.”

“A well,” Cal said to himself. “Isn’t there a well in the song?”

“What song?”

“Her song. One she used to sing when she was out catching kids or casting spells or something,” Cal said. “Father used to scare us by telling us she could steal our voices from a mile away, when we wouldn’t shu–”

“Shut up.”

Daisy rubbed at the glass, pushing her entire face to the cool surface. She focused on the bird necklace again and, confident that the house was empty, began to consider how she could get inside.

“Daisy.”

“Shh.”

“Daisy,” Cal said again, in a whimper.

“What?”

“Do you hear that?”

“No. What is it?”

“Exactly,” Cal whispered. “Nothing.”

He was right. A sneaking silence had collapsed over them, over the clearing, the house. Silence that was not an absence of sound, but something that crushed everything else. Daisy’s breathing throbbed in her head. Inside the house the fire had choked back to a few bluish embers in the grate. Her eyes were drawn to the edge of the well, as something pale and sinewy emerged from within. Long fingers began to unfold like the claws of a white crab. Daisy fell with a yelp from the window, colliding with Cal, before they clumsily dashed for the edge of the glade, to the gap in the undergrowth beneath a wizened hornbeam where they had crept in.

Daisy looked back at the house. The front door was open now. A curled white foot split through the dark and came to rest on the grass. Daisy dived into the trees behind Cal in fright. As they tumbled through thickets of arched, taunting brambles towards home, thorns scoring their hands and faces, a barbed lullaby pursued them over the tops of the trees:

No more birth

in the dry yellow earth

No more wishes

until you wash the dishes!

Find the well, find the smell

Where it most reeks

Find what you seek

in the dry yellow earth!

***

The flaxen ground of Lynchworth was – always – either scorched bone dry and impregnable by the sun, or sodden after an improbable deluge of rain. There was no in between. When the sun broke the rain clouds again, the soil instantly shriveled back to an arid, crumbling state. The time of rainfall was the time of the keyworm, a creature that, when stirred and excited by the drumming water, could nibble curiously right through the sole of a shoe. Or, if it was a lucky keyworm, find itself a toenail that was long overdue a trim. Daisy had never seen a keyworm, nor had she heard of anyone ever feeling one chewing on their submerged boot during heavy rain. Cal insisted one had once gulped down an entire bootlace from his left foot during a week of rain. He said he’d cut it in half with his knife and the two halves of worm wriggled away in opposite directions in the yellowish mud.

“If I hadn’t had my knife with me,” he gravely told Daisy now, “who knows what could have happened? I could have lost some toes, or worse! My entire foot.”

“Yes,” Daisy replied, bored with another of his tall tales, “thank goodness you weren’t eaten alive. By a keyworm. What did it look like?”

“I couldn’t really say, it all happened so fast,” Cal said seriously. “Did you know that if you chop up a bunch of keyworms, sprinkle them with salt and boil for two hours, then mash into a soup and then stir in some fig leaves and drink it, it makes you happy? That’s what my father told me anyway. He says that’s why they’re called keyworms.” Cal stopped to check the bottom of his shoe. “They’re the key to happiness. Daisy, did you know that? Are you listening to me?”

Daisy had stopped. They were on the outskirts of the town, on the road north towards the woods. A grey morning mist hung in the air like a persistent scab, too big to be picked. Daisy regarded the small, sand-colored house. Windows dark, the service hatch bolted shut. The word Violet’s painted blue on the plaque above. On the peeling fence bunches of flowers were tied, some wrinkled and liquefying, others freshly picked that very morning, already wilting.

“It’s been four days, barely,” Daisy said. She ran to the fence and began tearing at the flowers, twisting them in her hands and throwing them on the ground, stamping them into the cracked earth.

“What are you doing?” Cal said, almost laughing. He pulled her away from the fence.

“It’s only been … four days,” Daisy repeated, her hands trembling and bleeding from rose thorns. “And they’re already acting like she’s dead.”

“Come on, Daisy,” Cal said. “What else do you think could have happened?”

Daisy struggled to look Cal in the eye, but remained defiant.

“There was no evidence,” she said. “They found the flower and the necklace, that was it.”

“Then she must have left! That’s what I overheard Constable Irving say to old McRainey,” Cal argued, “that someone had done her in because she was asking for it – ow!” as Daisy thumped him, “– or she left town.”

“She didn’t leave town,” Daisy said. “She was happy here. She told me so. Everyone loved the bakery.” She blinked back tears. “They loved her too.”

“They loved her buns,” Cal said, stifling a giggle.

“She used to save me the last almond and cherry cake she made,” Daisy said, looking over to the hatch of the bakery again. “She was kind.”

Cal chewed on a fingernail and again checked the bottom of his shoe.

“I just worry all the time now,” Daisy blurted out.

“About what?”

“Everything, Cal! Everything.”

“But why?”

“Why? What do you mean, why? How can you not worry? If something bad did happen to Violet, doesn’t it terrify you? She didn’t do anything to deserve it. That means it could happen to you too.”

Cal shrugged.

“But why worry? You can’t do anything about it.”

Daisy opened her mouth to retort but only glared at him, confounded and irritated, a little saddened by his indifference. Then she said, “How can you not be scared all the time?”

Cal looked away, going back to chewing on his fingernail.

Daisy looked back to the bakery. She didn’t wish to say it again, so she thought the words instead, like she was afraid she might forget, or someone was trying to persuade her otherwise, twist her memory.

Violet was kind.

***

Violet Carrington ran a bakery in Lynchworth called Violet’s. It was very popular among the townsfolk, particularly at Saturday markets, where it was one of the busiest stalls of the lot; even on the hottest, driest days, which kept many potential visitors in the mercy of the shade. Poor Gwen Gaffney, eighty-two years old, while waiting in line one afternoon for one of Violet’s increasingly famous and sought after pear and hazelnut muffins, tragically died on the spot of heat exhaustion – such was the formidable (and, in that particular case, lethal) talent in Ms. Carrington’s baking skills.

Violet had long legs and a kind, round face. Her hair was light brown and she had an inviting smile, whether she intended to extend an invitation or not. She was also, as some talkative members of the community suggested, a “freewheeling” sort of woman. For instance, what precisely did one Harold Whitkins, dedicated husband of thirty-nine years to Mrs Whitkins, need with four Battenburg cakes a week? Did he personally need to collect each and every one? And what was it that kept that odd fellow, young Jonathan Reynolds, coming back every Tuesday afternoon to Violet’s, waiting patiently in the scorching heat, freshly pulled daisies clasped to his heart with both hands? Or Gallant Malcolm, that burly brute, who had proposed to Violet on three occasions (two of them in public), and had struck her more than once in a whisky-rage on a Friday night outside Hendall’s, and who on another occasion ripped her cotton dress down the front as she fled his hot, grunting breath – what had hoodwinked that ruddy-cheeked ruffian into a lusty fixation?

Cal and Daisy were largely oblivious to these goings on at the time, picking up only the vague mutterings of their parents across breakfast tables, but the two children were too busy trying to force down another mouthful of soggy oats or cremated bacon than to pay closer attention to the boring world of adults.

Daisy came to know Violet in a different way. Shortly after Violet arrived in Lynchworth and opened the bakery, Daisy (thinking that this naïve new girl in town would be an easy target) began regularly stealing from Violet’s. Stupid Violet, she would think gleefully, as she stuffed her pockets with iced buns and muffins, dusty bread rolls still warm from the oven, cramming an extra doughnut into her mouth as she took off down the path back into town, giggling strawberry jam down her chin. She stole from the bakery three or four times a week, choosing her moments carefully when the shop was busiest, thinking Violet stupider and stupider after every heist where she failed to notice she had been robbed. On the Monday of the fourth week of Daisy’s thieving spree, Daisy stealthily arrived at the bakery to find Violet’s market stall placed on the road outside. On a square linen napkin in the middle of the table rested a single cake. Daisy squinted at it in the sun. Almond and cherry; she knew them well. A small cake, but enough for one greedy child. Cal, who had reluctantly come along with her this time, warned Daisy not to eat it. Confident in Violet’s continued stupidity and her own genius as a cake thief, Daisy hungrily swiped the cake from the stall. She looked up at the bakery window as she took a bite. Violet smiled and waved through the window. Violet was, in fact, laughing mischievously, even triumphantly, and soon Daisy knew why.

She pulled the cake away from her mouth. Writhing around the mouth-shaped curvature she’d made in the sugary flesh was half of a fat, purple worm. Inside her mouth, the other half thrashed against her teeth. Cal howled with glee as Daisy spat out the mouthful of cake and worm, turning to glare at Violet, who called innocently, “See you again tomorrow?” Daisy skulked away, too embarrassed for words, Cal roaring behind her.

“A witch! Only a witch would do such a thing!” Daisy’s mother exclaimed, when Daisy told her of the worm incident, although she was unwilling to take matters further because she had, admittedly, turned a blind eye to all the cakes and seeded bloomers that kept mysteriously appearing in the larder. Daisy’s father, a man prone to first use his fists than his few words, slapped Daisy across the face with his knuckles. He waited until she was back on her feet before hitting her again. She stayed on the floor until he had left the room, wondering if he had beaten her for stealing, or for falling for Violet’s trick. All the same, he’d enjoyed his fair share of carrot cake.

The next day Daisy went back to Violet’s, but not to steal. She felt compelled to concede defeat; the trick with the worm she had found quite admirable. She waited in a pool of shade around the side of the squat building until all the customers had left, then approached the hatch through which Violet served her confections. Violet, dusty with flour, turned to greet Daisy with hands on hips and a fond smile on her face, as Daisy muttered something inaudible from behind curtains of her untidy blonde hair. Violet’s smile trickled from her round face when she saw the angry marks that Daisy’s father had left streaked across her jaw. Daisy, who had no use for a mirror, hadn’t noticed this herself, so she was a little perplexed when Violet’s hand sprang to cover her mouth in shock. She closed her eyes and turned away. When she turned to face Daisy again, she was holding an almond and cherry cake in the palm of her hand. She placed it through the hatch in front of Daisy, who eyed the cake suspiciously. Violet sliced the cake in half with a knife to prove that no slimy surprise lurked within. They each took a piece, and enjoyed them in silence.

***

Daisy continued to gaze at the shuttered bakery. Despite the heat of the sun now dispersing the fog, she felt a chill, an unpleasant spasm in her stomach, as she pictured Violet’s smile in her mind, as she often had since her disappearance. But Daisy couldn’t stop the image changing. Violet’s smile became strained, twisted; her face trembled and convulsed in pain, like someone was hurting her.

Cal was kicking up dust in boredom.

“Did you know that Errol Flannery thinks he has an imaginary friend?” he said. “Have you ever considered that I’m your imaginary friend? That would be pretty sad, wouldn’t it? That your only friend turned out to be imaginary.”

Daisy wiped her eyes and turned away from the bakery. She started walking back towards town.

She said calmly over her shoulder, “Have you ever considered that I’m your imaginary friend?”

“I want some sweets,” Cal said, ignoring her. “Let’s go to Halliwell’s.”

***

Lynchworth was a town always quick to succumb to rumors and speculation like a virus. A disease capable of animating and transmitting words, coagulating them into stories, mutating them into fantasies. Thus, as sure as the sun would rise to parch and crack the earth, when Violet’s failed to open one Tuesday morning, it did not take long for multiple theories to gather dizzying speed, despite the customary sluggish heat. Had Violet finally had enough of provincial life and returned to the affluent urban family she was rumored to have fled from? Had she perished in a disastrous baking accident? Had she finally given in to Gallant Malcom’s advances and he’d whisked her away on a honeymoon sailing trip? Hours of the bakery’s ovens being cold turned into days, and eventually Lynchworth’s sleepy authorities were bullied into action by Gallant Malcolm, who was, having been sighted leaving Hendall’s blind-drunk at four a.m. the night before the alleged disappearance, for the time being cleared of suspicion.

The bakery (and Violet’s tiny home above it) revealed no signs of a struggle, or of a hasty departure. A pale ashpetal flower, intricately woven around Violet’s necklace, was the only finding of significance in the investigation. The authorities failed to connect the flower to any external person or party of interest, discarded the lead and focused the investigation elsewhere. Which meant nowhere. After three days of chin scratching and poking around, police chief Flannery and the bewildered Constable Irving decided that Violet had most likely left town in a hurry. Or, given her tan and fondness for floral dresses, she had been kidnapped for nefarious and unspeakable purposes. To deter panic, he stressed that this latter scenario was very unlikely. He even suggested a lame middle ground version of events, where Violet had fallen madly in love with a handsome bandit cruising through town, dropped her rolling pin and jumped on the back of his horse, never to be seen again.

This infuriated Gallant Malcolm. Always one to fail in the act of thinking before the often regrettable act of acting, Malcolm resolutely decided the blame for his beloved Violet’s disappearance (and his only nuptial opportunity for hundreds of miles around) rested with “that odd fellow” John Reynolds, who never looked anyone in the eye and always laughed to the punchline of a joke no one else could hear. John Reynolds, who was widely known to wait for Violet outside the bakery to give her flowers, which Gallant Malcolm also determined must have been of the ashpetal variety. Weren’t they? It was never confirmed, but no one disagreed. Lynchworth experienced a collective shiver at the prospect of a young woman being taken or killed – a culprit must be named and caught, quickly! A fact Gallant Malcolm intended to capitalize on. For all his considerable shortcomings, he knew his town well. Therefore, despite Reynolds’ irrefutable alibi, Malcolm used the alleged fascination young John had with Violet as the fuel to put behind the boot he kicked in Reynolds’ door with, late on the fifth day after Violet was last seen. Gallant Malcolm strung John Reynolds up by his ankles in his father’s barn on the family estate and savagely beat him until he could hear ribs cracking in Reynolds’ scrawny torso. With no useful information extracted, Malcolm finished his bottle of whisky and fell asleep in the straw and cow shit. He woke early the next morning with restored vigor and a voracious conviction, cut Reynolds down and lashed him to his horse. His notion was that perhaps Reynolds would give up Violet’s whereabouts while enduring pain in front of an eager audience.

That morning the heat was ferocious. The hard yellow earth on which the town was built sighed under the weight of its apathy; outside the subsiding town hall, a cockerel walked around in a circle with very deliberate, accurately placed steps in the dust. It pecked twice at the same spot on each rotation, squawking indignantly with a fluttering hop as Gallant Malcom rode into town, dragging John Reynolds behind him.

By the time he was cut loose, collapsed outside McRainey’s Butchers to a horrified and thrilled Lynchworth thoroughfare, Reynolds was so unrecognizably covered in yellow dust and blood he shimmered gold like a divine totem. Gallant Malcolm continued his campaign of beatings, but Reynolds by this time could only produce scarlet bubbles from his mouth, or cough puffs of yellow grit. Malcolm, who had not really planned this far ahead without a result, noted the palpable lack of support he had otherwise expected from the crowd watching his valiant endeavor. He briefly wondered if he should have waited until after Hendall’s had opened before dragging Reynolds into town. Violent entertainment does go down easier with a drink. Head pounding under the morning sun, Malcolm retied Reynolds to the back of his saddle and galloped north in the direction of the ravine – the first place his polluted mind could think of that would provide the required spectacle. As he had hoped, a band of drama-hungry townsfolk followed, Flannery waddling not far behind. With his audience in place, Gallant Malcolm held John Reynolds over the edge of the ravine, a knife to his throat, and once again demanded to know the truth of what he had done to Violet. ‘What monstrous deeds have you subjected poor Ms Carrington to, you debauched scoundrel! Tell us! Tell us where she is!’ he boomed, voice ricocheting across the ravine. Reynolds only wheezed in response, blood bubbling in his throat as he reached out with both hands towards the onlookers. Flannery sighed, arms flapping, powerless. Malcolm, furious that things still weren’t going his way, had no choice in his mind but to push the blade through John Reynolds’ bruised ribs and drop him over the edge.

***

Flies hummed a laconic tune at the bottom of the ravine. Daisy could hear them before she saw John Reynolds’ body. The bottom and top halves were twisted the wrong way around. His stomach was fat, as if he’d just eaten a huge lunch, which was strange because everyone used to whisper how thin he was. From his purple face, one of the eyes was gone. Flies twitched in and out of the cavity. Cal doubled over and heaved between his shoes.

“Finn Robbins told me yesterday that he heard singing from down here. Reckons it was the witch from the woods,” Daisy said. “Bells and dishes … he said she was singing … about…” She vomited too. “Do you think the witch actually exists?”

Cal wiped his mouth on his sleeve.

“I heard Malcolm came back for the eye,” he said.

“How could he have done that?” Daisy gasped. “They locked him up.”

“Do you think John Reynolds hurt Violet?” Cal said.

“No,” Daisy said. “I don’t think he did.”

Cal squinted in the sun, thinking.

“Does violence run the world?” he said, finally.

“Dunno. Probably,” Daisy said, straightening up.

“If it does, do we have to stay here?”

“What do you mean? I don’t think we have much of a choice.”

“Don’t we?”

“So now you’re feeling scared?” Daisy said, irritated that Cal was more afraid of a man now in jail than the unknown person responsible for Violet’s disappearance.

As they were climbing out of the ravine, Cal said, “Did you know that people say the witch is over a thousand years old? Do you believe that?”

***

In the days after Violet’s disappearance, as any hope of finding her began to seep away like rain into the hard earth, Daisy wandered aimlessly through and around Lynchworth, willing the sun to evaporate the dread crawling over her skin. Cal was leaving his house less often, probably due to her confused and sombre mood, Daisy suspected, while her mother was crying more, her father quicker to twitch into violent rage. She meandered with an emptiness that had nothing to do with hunger. Normally she would have gone to visit Violet. She felt angry and useless, afraid of walking alone when venturing too far from town, through the woods or along the lonely cliffs over the beach, but remained defiant to the thought of a threat lurking in the shadows, and would not shut herself away. She could bite and scratch and kick effectively, as Cal would testify.

Daisy also couldn’t stop thinking about ashpetal.

Ashpetal leaves were as white as a thing called snow, a soft delicate stuff Daisy’s mother told her fell out of the sky in some parts of the world. Daisy didn’t quite believe this. It sounded like something Cal would come up with. Thin blue veins ran through the circular ashpetal leaves, which wreathed a flower of blood red petals that created an uncanny depth to the plant. It was hypnotic, Daisy had discovered, as she stood in a field of ashpetal, staring into one she’d plucked from the ground. It was only two days since the murder of Jonathan Reynolds and, eager to escape the perpetual bristly exchanges between her parents one evening, she’d snuck out and headed for the woods, for silence and for solitude, trying not to let the memory of John Reynolds’ corpse overwhelm her. She suspected that she and Cal should not have gone to the bottom of the ravine, but the ghoulish temptation had been impossible to resist. In her wandering she discovered the field coated in the flower, her heavy heart suddenly racing with excitement as she realized that this must be where the flower left in Violet’s home had come from, for flowers like this were rare in Lynchworth. Nothing that delicate could survive the crusty heat. But who could have left it? She hoped it was Violet herself, meaning her friend was alive and well, and who must have left the flower-necklace as a clue for Daisy, for Violet knew how Daisy liked to wander the forests and dusty hills surrounding Lynchworth. But why had Violet chosen to retreat from her life in the first place? To escape Malcolm? Or something else Daisy was yet to discover?

She took a mental breath.

Or an enemy had left the flower, meant as a villainous taunt. The last remnant of Violet in the world.

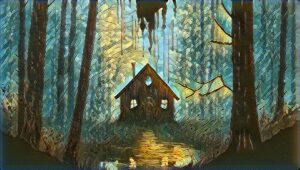

Pushing the thought away, Daisy realized it was raining. Rain heavy enough to make her shoulders curve. She could feel herself sinking. Across the field of speckled white, a black figure, reduced to a shimmer in the haze of the rain, was watching her. Fear-stricken, Daisy retreated into the trees and the figure vanished. Sheltering from this typically violent downpour, Daisy found herself on a path unfamiliar, disoriented by the branches winding up into the sky like black veins. When she reached the clearing the rain stopped, leaving a throbbing, damp silence over the forest. Ahead of her was the small house. The witch house, just as the stories and the songs said. Deep in the dry woods, where Madame Sosostris dwells. It sagged idly in the sallow mud. It reminded Daisy of a set of crooked teeth. She looked through the window, but only for long enough to glimpse a barren fire grate, the furry layer of dust that covered every surface, when sunlight surged over the clearing. Daisy squinted up into the sky, feeling fresh droplets on her face, to see a black, dripping shape crouched like an abhorrent bird on the roof of the house. A pale, muscular arm lashed down at her face; she backed away just in time, her feet slipping out from under her. When she turned back to the house, face smeared with mud, the figure on the roof was gone.

***

The rain fell again, merciless. Daisy lurched through gloopy yellow mud back to town, to Cal’s house. She skidded to a halt and shook herself off like a mutt on the porch; his mother, broom in hand inside the front door, tutted through the soggy cigar pinched between her cracked lips. Cal, sitting cross legged while chipping dried mud from the bottom of his shoe, shrugged when Daisy finished her breathless story. Then his face lit up, mind already somewhere else, and said, “Did you know that somewhere up north there’s a giant so big that her heart only beats once a year?”

“The field, the ashpetal … I’ve never seen so many flowers in one place. Not alive, anyway,” Daisy continued. “I think … it’s something to do with … her.”

“Who?”

“The witch. Madame Sosostris,” Daisy whispered.

Cal stopped chipping at the mud, as his mother inside huffed in spiteful laughter and spat on the floor.

“No one has seen the fortune teller in decades,” she wheezed, “if she ever existed in the first place. Ha.” She spat again.

Daisy ignored her.

“Did you know–” Cal began.

“Shut up!” Daisy and Cal’s mother both snapped.

Cal scowled at the hammering rain. Daisy waited for his mother to start sweeping away from the front door.

“I’m serious, Cal,” she said, her voice low.

“Oh, come on, Daisy. She’s not real, she’s just a story to scare us home on time. A fairy tale.”

“But I saw her house!”

“So what? It’s just a house. Could be anyone’s,” Cal said.

“There’s something in the woods, Cal.”

“What?”

“I dunno. I saw something. First in the ashpetal, then…”

“Was it the witch?”

“I don’t know.”

“What did it look like?”

“I couldn’t see it very well. It definitely had arms.”

Cal sighed.

“I’m not making this up!” Daisy protested. “Think, for once. The only thing left of Violet was her necklace, with an ashpetal flower wrapped around it. Most people in Lynchworth have never even heard of ashpetal, let alone seen it! And then I find a whole field of them, near the witch’s–”

“Alleged house.”

“Don’t you think it’s strange?”

“Coincidence.”

“It means something, Cal. It means something. The witch, or that thing in the woods, whatever it is, knows something about Violet. Why else would it attack me?”

“It attacked you?”

“Almost. But do you know what that means?”

“Nope.”

“It’s protecting something!”

“Doesn’t mean she’s alive,” Cal mumbled.

“Excuse me?”

“It doesn’t mean she’s not dead, Daisy!” Cal yelled.

His words were quickly swallowed up by the rain. Daisy’s heart gave a very sudden thud inside her ribcage, hard enough to make her gasp in surprise. She turned away from Cal.

After a few long moments, her back still turned, she said, “Will you help me or not?”

Cal jigged his bent knees up and down in frustration, undecided.

“We have to try, Cal,” Daisy said. “We have to try something.”

The rain stopped. Before the sun had even begun to sprinkle its light over the world, the tearing of the drying earth could be heard in soft, pained whispers beneath them.

Daisy said quietly, “She would have done the same for you.”

***

Gallant Malcolm bargained his way out of the jail house by promising a bottle of his finest single malt to Constable Irving, who was working up quite the sweat of nervous withdrawal as he endured a painful night watch. Together they left the jail house and headed towards Hendall’s, Malcolm still stained maroon with the dried blood of Jonathan Reynolds. Inside the tavern, heads turned as Malcolm headed for the bar. Accompanied by the police constable, no less! No cuffs or shackles of any kind to be seen on this undeniable murderer, who must have come to some agreement or other with the authorities.There had been a misunderstanding of some kind, perhaps it was all an accident – Reynolds slipped and fell into the ravine, falling against Gallant Malcolm’s blade in his downward trajectory. Wealthy chap is that Malcolm fellow, simple bribe could have done it…

Such were some of the foggy theories exhaling from the punters’ nostrils in Hendall’s that night. It was all too hot to really commit to thinking about. An inescapably spongy heat was gripping the town, hemmed in with the pervasively sulfurous scent of rotting leaves. Malcolm sank his first whiskey and knocked on the bar with the glass for another, the burning liquid helping him attune to the heavy mood of the room: a turgid paralysis, such was the influence of the mystery and possible grotesqueness of the manner of Violet Carrington’s disappearance. But poor Malcolm, already starting to prickle with his third shot, typically mistook this sombre atmosphere as a requirement for action, rather than a time of reflection and mourning, for Violet and perhaps for a world not as they thought it to be; a feeble but determined attempt to understand what had happened – how and why one of the best of them had come to suddenly leave or, as most now believed, be snatched away. The most crucial thing of all that Malcolm failed to grasp, and never would while the town of Lynchworth eventually would accept, is that there was no true understanding to any of it.

Nevertheless, Malcolm proceeded to gulp down his fourth shot and shatter the glass on the floor. No one flinched. They were expecting it, and the spitting speech of rage and grave indignation that followed as Malcolm tried to stir the drinkers of Hendall’s into action. But no one would be following him up to the ravine tonight. Irving seemed to have forgotten his occupation, superfluous as it was. The only reaction to Malcolm’s provocation came from a gurgling man in the corner, who Malcolm seized by the front of his filthy shirt and shook to increase his volume. But the man was blind drunk and only able to utter certain words and phrases, variations of:

Fucking bitchhh…

Witches. All of them—

She’s a witch! Can’t trust…

All of them—!

Witches.

The man was David, Irving informed Malcolm, long-time assistant at McRainey’s, who was on an impromptu bender after holding his wife Martha’s hand on the stove when she told him she had no idea where their daughter Daisy was – probably off somewhere in search of that witch in the forest, the girl Violet she kept harping on about, along with that dense dunce, what was his name again, yes, Cal. A waterlogged seed in Malcolm’s mind began to sprout and take root, a memory of Violet mentioning the girl Daisy who used to steal from her bakery, the two becoming friends soon thereafter. Malcolm pressed David further, pouring drinks into his mouth and yielding more fucking witches/bitches murmurings, but now also: ashpetal.

His own drunkenness eroding the evident tenuousness of these findings, Gallant Malcolm found himself feeling two new feelings: excitement, at the slim possibility of a new lead and new reason to cause self-righteous carnage, and a gnawing annoyance that a mere child – a girl – might know something about Violet he didn’t, or worse, could actually be a step closer than him to solving the mystery.

And so Gallant Malcolm stomped out of Hendall’s into the stifling night, turned and started to walk, hoping he was heading in the direction of the woods.

***

Daisy emerged from the eaves of the forest, skin tingling from a thousand scratches and thorny grooves sustained from tearing through the underbrush, terrified that Madame Sosostris, or whatever that thing was, was just a few steps behind them, singing that eerie, mellifluous song. Cal leaned over, breathless. Daisy looked over his arched back to see the dim orange lights of Lynchworth at the bottom of the hill, like everything was normal.

“Is she still behind us?” Cal wheezed.

“I don’t think she followed,” Daisy said.

“Is it really her? Did you hear the song?”

Daisy didn’t reply.

“Do your parents make you do the dishes?” Cal said.

Daisy remained silent. She was starting to realize what they had to do.

“Daisy? What now?” Cal pressed. “Daisy?”

“We go back. When she’s not there,” Daisy said firmly, “I saw her necklace, Cal! Violet’s necklace. And there’s a well, just like in the song –”

“Are you mad?” Cal protested incredulously. “There’s nothing down there, Daisy—!”

“Shh!”

Thudding footsteps and hollow breathing, coming towards them up the hill. Daisy pulled Cal back into cover of the trees as the hulking form of Gallant Malcolm broke into the moonlight, gaunt and unshaven and whisky-eyed, knife gripped at his side. His huge, bloodstained chest ballooned in and out, hair wild and glowing. He looked quite mad. He stared straight at them, seeing only the murk of the trees.

“Is that you, witch?” he spat, and Daisy felt Cal tremble beside her. Malcolm laughed. “Or is it someone pretending?”

Eventually he moved off and pushed his way into the trees, cursing and spitting.

“How is he free?” Cal finally whispered. “After what he did.”

“We have to go after him,” Daisy said.

“What? No way—”

“Cal, we have to. What if he hurts the witch? We need her to find Violet.”

“You don’t know that for sure, Daisy,” Cal groaned. He’d stepped out again from the trees, towards Lynchworth. “He’s a murderer, Daisy. Do you realize what that means?”

“Of course I know what it means,” Daisy said. “What do you think will happen if he finds Violet instead? They’ll kiss and make up?”

Cal looked down at his shoes, perhaps hoping that a keyworm might emerge and nibble on his toe to distract him.

“Did you know–?”

“Stop! Stop with your stories!” Daisy burst out furiously. “I’m sick of it, just shut up! They don’t mean anything.”

Cal laughed but quickly faltered. He looked like he was about to cry.

“I can’t go with you, Daisy,” he said. “Not this time.”

Then, without looking at her again, Cal turned and ran.

***

Gallant Malcolm was never the man with a plan, always a slave to impulse. But even he, in his boneheaded way, had a sense that something was coming to an end, as did poor terrified Daisy, once again tearing through a forest that seemed to leer down at her mockingly. Malcom was approaching the front door now, knife held aloft in front of him, trying to decide if the whispering he could hear, louder and louder, was in his head or seeping from a pair of hidden lips.

No more birth, in the dry yellow earth came the soft words, like the beating wings of a moth.

Malcolm tried the door to the house. It was locked.

Find the well, find the smell—

“Curse all of you witches and whores and bitches,” Malcolm roared into the sky; a proclamation of his manifesto, his life’s work.

Where it most reeks—

Malcolm plowed the door down with his boot. The smell surged out and he fell back, retching. An elastic cackling came from behind him. Malcolm wheeled around in the dirt, coughing, to see the angular form of Madame Sosostris. Dressed in ragged black, face hidden behind curtains of lank, heavy hair – just as she was drawn in the story books, how he had imagined her as a boy – grey, bleeding lips just visible, giving shape to that last couplet of her song—

Find what you seek

in the dry yellow earth!

***

Daisy knew she was close to the glade when she heard the maniacal, almost euphoric, caterwauling. She arrived to see Malcolm hunched over, frantically throwing his blade into a vaporous form again and again, but there came no sound of impact, no thump of punctured flesh and blossoming blood no matter how many times he stabbed, grunting with the effort and bewilderment, while a cacophony of shrieks escaped from beneath him.

Daisy ran for the house. The witch had climbed out of the well, maybe that’s where Violet was hiding too. She had a foot inside when the smell coursed over her face and into her nostrils, swarming her lungs, just as Gallant Malcolm’s hand caught her arm so hard that it nearly bent to break. She had never seen such a look in a man’s eyes as she saw then in Malcolm’s, not even in her father’s before a beating.

“Where is she?” Muscles in his jaw pulsed under the skin like worms. He put the knife to Daisy’s throat in answer to her silence. “Where… is my Violet?”

“She isn’t yours,” Daisy replied, trying to squirm free.

Malcolm’s face slackened and stuttered forward, as something collided with the back of his head; he released Daisy and swung around with the knife, the blade entering Cal’s left ear so far that the tip was visible exiting his right. Cal coughed in surprise and dropped the second rock he was about to throw. Daisy stared at him, unable to scream. Malcolm released the knife and stepped back from Cal, who dropped to his knees. His head fell slowly forward and became still, like he had fallen asleep. Malcolm looked down at his hands for a moment, before clearing his throat and turning back towards Daisy, who saw a brief glimmer of despair across his flat face before his predator’s eyes locked onto her.

Daisy scrambled the rest of the way into the witch’s house. She looked back, beyond Malcolm’s approaching bulk, for another look at her brave friend before letting herself fall down, down into the well.

***

Peering over the edge of the well, Gallant Malcolm exhaled with bemusement. He listened again. No cry out in pain or for help; only stillness from the clotted darkness hanging just a few inches beneath his fingers. A darkness that judged him. His mouth was dry. He left the house in a quick step as the rain began. He strode back to where he had left the witch, past the foolish dead boy with the knife in his head, still upright on his knees with head bowed, but the witch was gone. Had she been there at all? Where she had lain was a patch of brown earth. Malcolm hunkered down and saw that the surface of the earth had been torn away, revealing the pullulating mass beneath. Malcolm had never seen so many keyworms in one place, all glistening and writhing in the mud. The friction of their wet skin produced an unsettling, rubbery sound. One wriggled free and landed on his arm. From its folds of yellow-brown skin protruded a ring of black teeth which began to methodically slash at and burrow into his arm. Another propelled itself to his neck and latched on. As thunder swelled in the sky, soon every inch of Gallant Malcolm’s skin was being torn open and gorged on by keyworms and he merely exhaled, accepting of it, and fell on to his back. He pushed his head back into the mud to see the inverted image of the dead boy, the last he would see. A winged shape emerged from the witch house, cutting through the downpour over the boy’s head and disappearing into the night. Thunder cracked and silent flames enveloped the house. The keyworms slowed their feasting on Malcolm’s flesh and he was kept alive long enough to watch the house and legend of the elusive Madame Sosostris, fabled witch, creature-woman of the woods, char and crumble to dust, then into mud.

Now he could rest, and sink – the brave, gallant Malcolm – into the wet yellow earth.

***

Daisy can hear the ocean. Soft waves. A melancholic song in the night.

Except.

There is no night or day, wherever she is. Only whiteness, an emptiness. She wants to cry. Is this the only place Violet could hide? A safe place that is only so because it’s a place of nothingness, of utter absence. Daisy wails. She can’t hear her voice. The sound of the waves surges, a violent swell as a storm somewhere brews, threatens to swallow up the forest, Lynchworth, maybe the whole world and who would care? At least the monster waiting above would be gone.

In a rush the storm vibrations surrender to silence. Daisy looks down at Violet’s market stall. A single cake occupies it. Daisy looks up again at the searing green gaze of Madame Sosostris, alabaster and cadaverous and somehow elegant, untidily framed by her mane of chaotic black hair. The witch is unmoving, but breathes deeply. Daisy struggles to focus on her face. It is a changing face. Her breathing is the only sound. It fills the world and Daisy’s ears, trying to tell her something through its painful wheeze. Daisy tries to form words, but they are stolen away from her mouth.

She is beginning to understand, and is not afraid. She reaches out and gently turns the cake. It is cut in half. A fluffy cream rests in the center, hidden from all. Daisy takes a half in her hands and looks up to Madame Sosostris, whose hair begins to ripple with the sound of the returning waves, black specks flaking away like dry seaweed, until her hair becomes light brown. Her sharp features round and soften, as she holds up her half of the cake, smiles at Daisy, and they are both ready to eat.

This story previously appeared in Dark Horses Magazine No. 27 – April 2024.

Edited by Marie Ginga

Tom Preston (he/him) is a writer from Dorset, UK. His short fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in Hearth & Coffin Literary Journal, Litro Online, Dark Horses Magazine and Dagda Publishing. Two of his poems were featured in Forward Poetry's 'Light Up the Dark' edition. He lives in London.